This Article From Issue

September-October 2001

Volume 89, Number 5

DOI: 10.1511/2001.34.0

Biologists and the Promise of American Life: From Meriwether Lewis to Alfred Kinsey. Philip J. Pauly. xvi + 313 pp. Princeton University Press, 2000. $29.95.

In 1892, the dashing, cosmopolitan geologist Clarence King offered readers of The Forum (a New York literary magazine) a prescient look into the future of America. With expansive vision and a surveyor's eye—cultivated at Yale's Sheffield Scientific School, under the tutelage of Harvard geologist (and zoologist) Louis Agassiz, and as first director of the U.S. Geological Survey—King heralded the century's end as "the age of energy," adding that "next will be the age of biology."

Forty-two years later, in Technics and Civilization, the influential historian, social critic and regional planner Lewis Mumford similarly looked forward to a coming "biotechnic era." America, the product of both the machine and nature, would, Mumford believed, be transformed through science and technology into an idyllic landscape of decentralized, productive biogeographic regions.Biologists and the Promise of American Life is an episodic history of how American naturalists, federal scientists, experimental biologists and high school biology teachers have contributed to and shaped this underlying vision of America as promised land. Ambitious in its scope, Philip J. Pauly's book grafts the stories of local and regional communities of scientists onto a narrative stock of national improvement and progress. Culture, understood in its 19th-century meaning as cultivation, is the common root that rather loosely binds these local histories together.

King and Mumford were in one sense looking backward into America's future. America was, after all, "nature's nation," as Thomas Jefferson proudly proclaimed in his Notes on the State of Virginia. But to European colonists and later generations that forged a nation, America's destiny rested not in nature's purpose unfulfilled. English colonists viewed their agricultural improvement of the land as an act of providence and entitlement. Two centuries later, Ralph Waldo Emerson's remark that art is "nature passed through the alembic of man" echoed a common refrain—that cultivated nature offered the promise of American life.

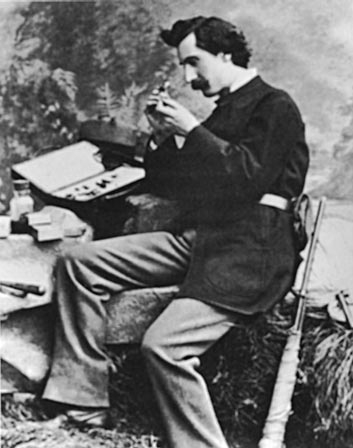

From Biologists and the Promise of American Life.

American biology, Pauly writes, "was an ongoing effort on the part of scientists in the United States to 'culture' the western hemisphere and its organisms—to influence the distribution, reproduction, and growth of plants, animals, and humans, and to improve them." From Asa Gray's efforts to unify the flora of North America to those of teachers at DeWitt Clinton High School to instruct students in biology as a lesson in adaptation, assimilation and progress, biology has been an important tool in serving national agendas and goals since the American Revolution. Although historians in the past have largely interpreted biology as a conservative social weapon in American culture—one that has reinforced slavery, racism, cutthroat capitalism and anti-immigration sentiment—Pauly offers a progressive reading that argues for the importance of American biology in the establishment of a "liberal, secular, and humane nation."

The book is divided into three parts. The first follows the shift in natural history from its Boston center in the antebellum period, under Agassiz and botanist Asa Gray at Harvard, to its increased prominence in the golden age of federal science in Washington, D.C., during the post–Civil War era. The second section details the development of an academic culture of biology at the end of the 19th century, centered at institutions such as the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, where, Pauly suggests, university biologists became disengaged from questions related to societal problems, either at the local or national level. In the book's last section, Pauly focuses on a few select examples—metropolitan high-school biology, eugenics and reproductive science—to explore how biologists attempted to reassert a place for themselves and their science in American culture and politics from the Progressive Era to the Second World War.

Whether writing about the biological basis of national unity, nativism or sexuality, American biologists were, as Pauly rightly observes, tackling "big questions" that took them well beyond the local confines of the field or laboratory. Biologists and the Promise of American Life offers us glimpses of that broader picture, but it never quite delivers in offering the grand, synthetic narrative the title and introduction imply. While Gray and Agassiz, for example, debated whether unity or diversity represented North America's biogeographic history and political future, other New Englanders such as naturalist/philosopher Henry David Thoreau were also reflecting on the place of nature in American life. And although federal naturalists such as John Wesley Powell and Lester Ward looked to evolution as a guide for democratic government, theirs was a "progressive" vision that had questionable implications for Native Americans (this story, like many others alluded to in the book, is left unexplored).

In focusing on select case studies, Biologists and the Promise of American Life offers a valuable contribution to the local and regional history of biology in American culture. But a grand synthesis that weaves together the many meanings of nature and biology in American life will need more than the intimate and detailed knowledge of the local natural historian. It will require more attention to a panoramic view of biology across the diverse contours of America's changing landscape and a breadth of vision akin to the surveyor's eye of Clarence King.—Gregg Mitman, History of Medicine, History of Science, the Institute for Environmental Studies, and Science Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.