This Article From Issue

September-October 2016

Volume 104, Number 5

Page 315

DOI: 10.1511/2016.122.315

THE CAMERA DOES THE REST: How Polaroid Changed Photography. Peter Buse. ix + 308. University of Chicago Press, 2016. $30.00.

Point , click . The gesture is now so familiar that its onetime novelty seems distant and improbable, even though—when I nudge myself from the dreamlike state of digital ubiquity—I well remember photography as a significantly more complex process. In many ways Polaroid paved the way for this state of photographic affairs, even as it has been largely sidelined, after two bankruptcies in the first decade of this century, from what might have been a victory lap.

Critic and theorist Peter Buse’s fine examination of the cultural history of Polaroid technology, The Camera Does the Rest , considers the societal forces at work as the company succeeded and failed, from the launch of its first camera in 1948 to its existence today. Buse considers the cultural forces Polaroid was responding to as well as those it helped shape as a highly influential global brand. It built its reputation on technological innovation cultivated within a “model of perfectionistic deep research” that was, Buse explains, “central to Polaroid’s ethos.” To call Polaroid the Apple of its day would be reductive: Steve Jobs patterned himself after company founder Edwin Land, openly citing him as a role model. (For more on this topic and on Land himself, Christopher Bonanos’s book Instant: The Story of Polaroid is well worth a look.) Perhaps it’s more accurate to say that Apple is the Polaroid of our moment.

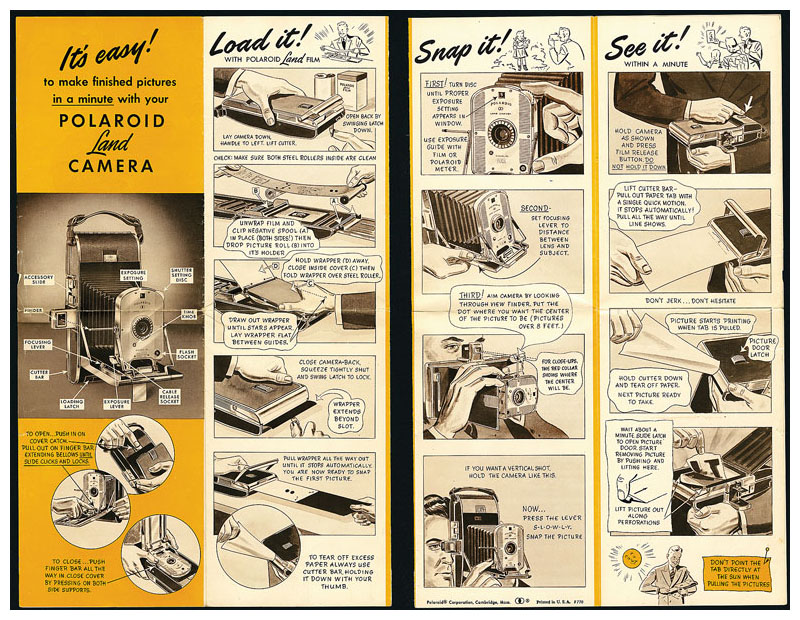

Land, who left his chemistry studies at Harvard to devote himself to inventing an inexpensive polarizing filter, originated the field of instant photography—?that is, photography that features in-camera development to produce a print immediately—with the release of Polaroid’s first camera in 1948. He and a team of scientists, engineers, and designers continually refined the company’s cameras, regularly producing breakthrough innovations, such as a sonar-based autofocus system; a 20x24 large-format camera, which became a darling of photographers; and the first truly one-step instant camera, the SX-70, which developed in daylight, without any intervention by the photographer (for example, pulling the print from the camera or removing a backing from the print).

Land’s sense of showmanship helped cement Polaroid’s reputation for innovation. Buse notes that he was often depicted in the media as “some sort of scientist-hermit,” despite a lack of evidence, possibly because “commentators…automatically read Land in terms of the popular image of the scientist as lab-bound, socially awkward, and preoccupied with his experiments to the exclusion of all else.” In truth, his demonstrations of Polaroid’s latest innovations, especially those presented during highly anticipated, carefully staged annual meetings, were part of a tradition harking back to earlier figures, such as Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla. To apply the shy scientist stereotype to Land, Buse says, is “to obscure the ways in which he was really a throwback to a previous model of the scientist-inventor as public figure.” Land understood how crucial demonstrations were for his company’s defining product. Instant photography is very much about the social moment: sharing the instant when an image is captured and the developing time as it comes into view. Often, too, it is about sharing the physical image, as Polaroid users often gave away photos spontaneously. Polaroid extended its emphasis on demonstration into the sales field, where its representatives would photograph shoppers and offer them the images to keep. In 1960 alone, Polaroid sales staff gave away 1.5 million snapshots.

The Camera Does the Rest is foremost a social analysis of a technology, or as Buse puts it, examining “a technology in culture.” Although he includes mechanical and scientific details along the way, Buse’s real aim is to consider the broader context in which instant photography was presented and received, how people used the devices, what they thought about it, and what they continue to believe about the medium. Scholarly and philosophical, the book is an intriguing read, although not a casual one.

Today Polaroid endures as a revenant of its former self, its research and development functions having shut down a decade ago. Digital photography is widely considered the culprit, and it was instrumental in Polaroid’s decline, which Buse narrates enlighteningly. Yet he also wisely reframes the discussion. “It is not a question of when digital did in Polaroid,” he explains, “but what remains in digital of Polaroid.” Buse’s answers offer insights into our interactions with technologies over time, as well as new ways of understanding the evolution of contemporary shutterbugs.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.