Beauty Is Only Feather Deep

By Catherine Raven

Was the bald eagle really the best choice of national symbol? A closer look at the habits and evolutionary lineage of this American icon casts doubt

Was the bald eagle really the best choice of national symbol? A closer look at the habits and evolutionary lineage of this American icon casts doubt

DOI: 10.1511/2006.61.392

At first, all I saw were a couple dozen people shuffling around, most fumbling with binoculars, a few already staring up at the sky. I generally avoid crowds, especially tour groups, when I'm out pursuing wildlife. But these people, varying in age, size and couture, were clearly disorganized. Convinced of their harmlessness and curious about the object of their attention, I parked next to them (at the Lamar River pullout in Yellowstone National Park), perched on a boulder about four meters away and quickly discovered the nature of their confusion. Although it was midday, a tiny white star seemed to be flashing in the cloudless, sapphire sky. After focusing their binoculars, the onlookers realized the star was a bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), and a symphony of "oooos" and "aaaahs" began. Then, within a few minutes, a raven appeared. A protracted fight ensued during which time the relatively small raven demonstrated agility, tenacity, and bravery (a judgment that any bird expert would confirm as unbiased, my surname notwithstanding). The bald eagle demonstrated the better part of valor and fled.

Stephanie Freese

"Yessss!" I shouted spontaneously, thrusting my right fist forward to salute the raven's coup, at which point the entire crowd turned toward me and stared as if I were a devil worshipper. Sure, I've received worse looks, but never by so many people simultaneously. I would have avoided those malevolent expressions had I shown up 200 years earlier, when the only people in the valley were Indians. In those days, a person could choose to raise a hand to honor either the raven's skillfulness or the bald eagle's beauty. But the most revered bird in this area would likely have been the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos). Countless natives probably rode through this valley with golden eagles painted on their horses. Today, tourists ride through with bald eagles painted on their motorcycles.

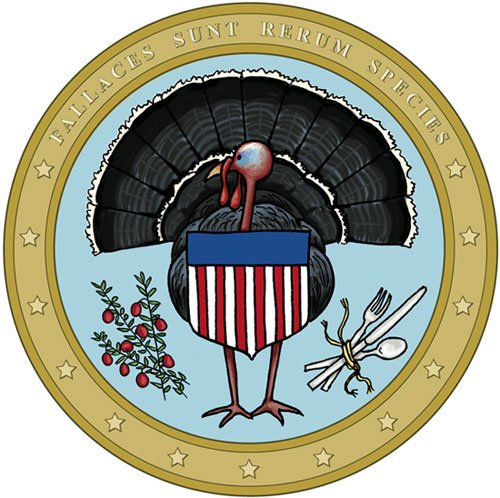

The transfer of allegiances began with Thomas Jefferson, who appointed the bald eagle to serve as the national emblem for the new American nation. It was a classic example of the outdated practice of physiognomy. Now considered a pseudoscience and an excuse for racism, advocates of physiognomy held that a person or animal's true nature was revealed by its outward appearance. Because of its white head and yellow eyes, physiognomists concluded that the bald eagle was fierce and noble. To his credit, Benjamin Franklin, the scientist, rejected this false logic, recognizing that the baldie was, in fact, a pirate and worse still, a "rank coward, commonly fleeing birds the size of sparrows." Franklin suggested that the turkey, a bird of many virtues, be used for the emblem instead. But Franklin's arguments didn't prevail: It seems our young nation was more concerned with symbolism than natural history, and the turkey had less charisma than the eagle.

Jefferson's ignorance of the bald eagle's feeding habits is difficult to justify. The eagle's lifestyle was accurately described in 1754 by the well-respected English naturalist Mark Catesby. In Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, Catesby identified the bald eagle as a scavenger whose favorite fishing hole was inside the nest of an osprey (Pandion haliaetus). Donating food to the bald eagle may be only a minor inconvenience for the osprey, an adept hunter, according to Catesby, that "seldom rises without a fish."

It's not surprising that baldies steal more than they hunt: They are not, in fact, true eagles. You can't be a member of that elite group (genus Aquila) with partially feathered legs and dubious feeding habits. The bare-ankled bald eagles are a type of sea eagle that diverged from the African vulture lineage only a few million years ago. Although they may at times hunt, they retain the vulture's ability to survive an entire lifetime on rancid, decaying flesh. They are obligated by neither physiology nor instinct to take live prey. By contrast, the golden eagle and osprey are both obligate hunters.

If by chance Jefferson understood this much natural history, he certainly didn't enlighten his buddy Meriwether Lewis before festooning him with bald-eagle insignia and sending him west to court the various Indian nations. Convincing potential allies that your intentions are honorable can be difficult when your totem is a bird who makes its living dispossessing property. Maybe Jefferson, prescient of future U.S.–Indian relations, enjoyed a little black humor. In any case, halfway through the expedition, Lewis became suspicious of the bird's purported nobility. In one of his journal's few sarcastic entries, he derides the baldie as both a thief and a scavenger. "We continue to see a great number of bald Eagles. I presume they must feed on the carcasses of dead animals, for I see no fishing hawks [osprey] to supply them with their favorite food."

For the bald eagle, ospreys are a reliable source of nourishment; for me, they're a reliable source of entertainment. Seeking such enjoyment, I sometimes slip down to the Yellowstone River near my home, one of many places where there is always an osprey. The last time I tried this, I didn't have to wait long before one shot like an arrow through the fall poplars. Skimming the water, black racing stripe flashing across its cheek, the bird plunged head first into the river, rose, banked elegantly and circled around to make another dive, this time rising with a trout. Not a trivial accomplishment.

For birds, aquatic predation is a difficult skill to master. Of the various species of large flesh-eating birds in North America, only two are aquatic: the bald eagle and the osprey. Nature clearly gave the latter better equipment. The osprey's barbed feet easily grab fish; its oily feathers resist wetting; sealing nostrils prevent water inhalation; translucent eyelids facilitate underwater vision; and black eye stripes minimize water glare. More significant, the osprey's talons turn backward, so that after it strikes a fish broadside and lifts it out of the water, the bird can turn the catch to face forward, making the load more aerodynamic. No other raptor uses this trick. Bald eagles are far less adept fishers overall, which is perhaps why they favor salmon runs where dead red fish, floating or beached, provide an effortless meal.

So baldies can't match the osprey in an aquatic habitat. Put them on land, and they'll fare even worse against the golden eagle. Not surprisingly, Lewis ended his honeymoon with the bald eagle when he began an affair with the "most beautiful of all eagles in America," the golden, America's only true eagle, whose feathers adorned the headdress of almost every Plains Indian chief. Baldies may successfully steal from the much smaller osprey, but never from the golden, a bird of equal size. Whether bringing down their own prey or feeding on dead or wounded animals, golden eagles rule. Lewis, for one, noted that on the golden eagle's approach "all leave the carcass instantly on which they were feeding." Interested in confirming Lewis's observations, I've hung out near carcasses. It's good enough entertainment that I'm willing to wake up before dawn and return to a scene repeatedly for several days watching until the play is over. Lewis was right: The two eagles enjoy strikingly different roles—the golden one feeds, the bald one cowers.

Americans who don't live among eagles and haven't read Lewis's journals can find enlightenment in Arthur Cleveland Bent's 1937 classic, Life Histories of North American Birds of Prey. "A fine-looking bird," Bent writes of the bald eagle, but "hardly worthy of the distinction [of being the national emblem]. Its carrion-feeding habit, its timid and cowardly behavior, and its predatory attacks on the smaller and weaker osprey hardly inspire respect." Bent's baldies-behaving-badly exposé also reveals that our nation's icon relishes vulture vomit. It's not that they find the vomit lying around; rather, they seek out vultures and force them to vomit. Then they eat the regurgitate. "Our national bird may still be admired," Bent suggests, "by those who are not familiar with its habits."

A few decades after Bent wrote those words, the time came when the bald eagle truly needed the public admiration it had so unfairly enjoyed. In the 1970s, DDT poisoning peaked, bald-eagle populations crashed, and organizations to save the bird rose up like earthworms after a rain. The tradition that Jefferson initiated was embraced by those well-meaning conservationists, who didn't believe Americans could love the bald eagle unconditionally. These activists saved the species but cemented a longstanding misunderstanding about the bald eagle's true nature. The three raptors I've discussed here might appear similar if given only a cursory glance. But ospreys are skilled fishers, golden eagles are keen hunters, and bald eagles are, well, mostly vultures. Bald eagles decorate the sky largely because they are vultures. Their white head feathers contrast with a brown body and suggest their naked-headed ancestry. And their soaring flight, though neither purposeful nor aggressive, is a vulture trait as well. Hunting birds spend more time flying low over the land, systematically searching for prey, a behavior known as quartering.

Floating over gorgeous places and enjoying the view, bald eagles seem to eschew responsibility. People might accuse me of that attitude, too, given that I spend so many hours leisurely watching birds. As a wildlife specialist, I am, technically, working during these times. Yet like the bald eagle, I adhere to routines that look more like loafing than real work. For me, it's a conscious lifestyle choice. I wouldn't deny that the turkey is the more appropriate symbol for Thomas Jefferson's concept of the nation, but for my idea of America, where the Constitution guarantees the right to pursue happiness, the bald eagle will do. After all, this is mostly how we spend our time, the bald one and I, diligently pursuing happiness.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.