This Article From Issue

September-October 2017

Volume 105, Number 5

Page 314

HERETICS! The Wondrous (and Dangerous) Beginnings of Modern Philosophy. Steven Nadler and Ben Nadler. 184 pp. Princeton University Press, 2017. $22.95.

What do the contentious treatises penned by a passel of 17th-century European philosophers have to do with how science is practiced in the 21st century? Much more than you might think.

At a glance, the disciplines of philosophy and science may not seem to impinge much on one another: Today, their most significant intersection is ethics. But in the West, science and philosophy were originally conjoined. The term philosophy sprang up around 1300 CE to refer to bodies of knowledge; for a time, the boundaries between disciplines remained indistinct. Eventually, the phrase natural philosophy emerged to represent study of the material realm—that is, any item, phenomenon, creature, or effect that is observable, whether it’s a spruce needle, a lightning bolt, a hedgehog, or the trajectory of a breeze. Only in the late 16th century did the term begin to represent a specific discipline; even then, connections remained between scientific investigation and philosophic inquiry.

So before science was called science (a term that didn’t take on its contemporary meaning until the 1800s), it was called natural philosophy, and the 17th century was its adolescence. These were the formative years of the Scientific Revolution, a movement that, in its turn, strongly influenced the Enlightenment. European scholars began to lay out foundational theories as part of a wider effort to grasp the basics of existence itself. In so doing, they generated theories that still inform our notions of what science is, what science isn’t, the role of science, and how scientists ought to regard their work.

A critical part of the process was the exchange of ideas among scholars: As they read one another’s books and shared manuscripts, scholars attached themselves to the ideas they agreed with, argued against and rejected those they disagreed with, and added their own ideas to the mix. The progression was heady, contentious, and far from linear.

In Heretics!, philosophy professor Steven Nadler and his son, illustrator Ben Nadler, remind readers of the vital connection between these 17th-century thinkers and how we continue to view science and its intersections with other fields. Their entertaining and thoughtful account of the European philosophical scene circa 1600–1703 presents a parade of philosophers—from Galileo Galilei, Francis Bacon, and René Descartes to Blaise Pascal, Robert Boyle, and Isaac Newton—as they exchange ideas, navigate alliances, and engage in scholarly feuds.

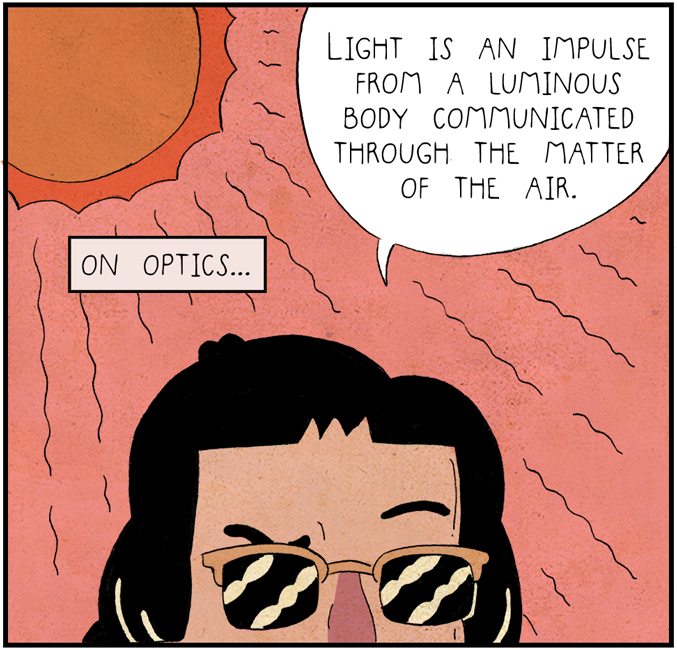

The Nadlers tell this story in graphic-novel style, and it’s a winsome approach. The book aims to present and contextualize a century’s worth of thought experiments about the properties and interactions of the cosmos, God, the human mind, the human body, and natural phenomena. No small task. By associating these ideas with distinct personalities and placing those personalities in conversation, the author and illustrator make their topic highly engaging while retaining sufficient complexity. They also take advantage of the opportunity to depict the world as each thinker envisions it philosophically. For example, the bearded deity shown carefully setting objects in motion to explain one scholar’s theories is banished from the scene when another theorist discusses his own, contradictory ideas.

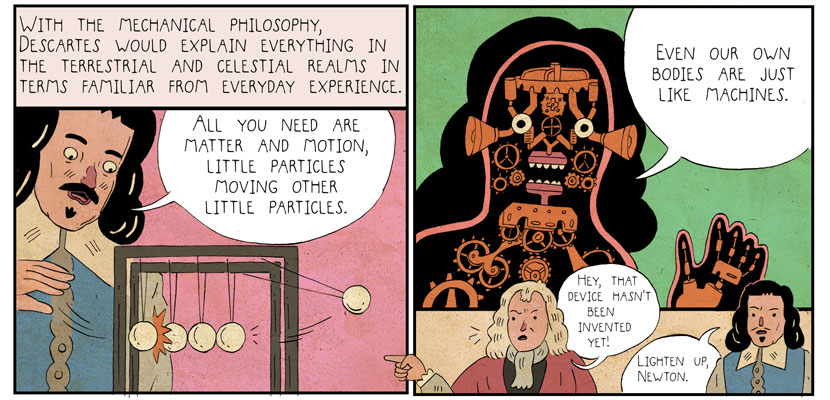

Taking full advantage of the format, the Nadlers use characterization, creative visuals, and humor to help convey the narrative. In an early scene, Descartes demonstrates one of his theories about matter and motion using a Newton’s cradle toy (see panels below). The familiar device drives Descartes’s point home instantly. But the Nadlers aren’t done with it yet. Anachronistically, Newton, who figures prominently later in the book, pops into the bottom of an adjacent frame to quibble that the toy itself is anachronistic. Descartes, irritated, suggests that Newton “lighten up.”

From Heretics!, S. Nadler & B. Nadler, 2017. Courtesy of Princeton University Press.

In these two panels, the Nadlers get across an early theory of matter, make it memorable with an injection of humor, and depict an aspect of the scholars’ personalities. The book’s epilogue conveys that philosophers came to regard Descartes as a “dreamer” and Newton, a “sage.” It’s a useful summation, but Steven Nadler’s canny characterizations in this early scene had already tipped readers off; he revisits these scholars’ distinct patterns of thought as the narrative unfolds, which proves helpful in assessing the men’s theories.

The liveliness of the narrative also helps convey the swirl of ideas scholars of the 17th century had to navigate and how theories tended to advance in a modular fashion. In the context of this ideological swap meet, advances that are especially original and fruitful stand out. For example, thinkers such as Robert Boyle began asserting that objects are made up of countless minuscule entities, or corpuscles; these tiny building blocks were generally believed to be motionless. In forming his own ideas, however, Pierre Gassendi reached back to Epicurus and drew on his concept of atomism; atoms, as Epicurus imagined them, were similar to Boyle’s corpuscles, but Gassendi did not believe they were simply inert matter. “They have weight,” Steven Nadler has Gassendi explain (as he stands under a falling anvil) and “an innate, natural, native propensity to motion that cannot be lost, a kind of propulsion or impetus from within.” The narrator goes on: “Just as Epicurean minima are surrounded by a void, so Gassendi’s atoms move through empty space.” Gassendi (presumably having evaded the anvil) steps into frame to add, “This allows atoms to move away from and toward each other, bouncing off other atoms but also getting tangled up with them and forming larger structures.” The moment comes across as a real breakthrough: The theory’s lineage is clear, yet it’s also apparent that Gassendi makes an impressive leap. Readers can then more fully appreciate why his theories went on to influence John Locke, who considered Boyle’s corpuscularian theory and Gassendi’s atomism as he formed his own ideas about objects’ primary qualities (that is, their defining characteristics, which he considered distinct from the qualities our senses can perceive).

In any epoch, thinkers must eventually drop a conjectural marker at the edge of the known territory and gesture at what lies beyond.

The book’s highly visual approach may also spur readers to connect 17th-century ideas to contemporary thought in fresh ways. For example, Ben Nadler’s depiction of row upon row of Earths—which he uses to convey German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s theory that Earth is only “one of many possible worlds”—immediately brings to mind the modern concept of the multiverse. Although Heretics! doesn’t mention the multiverse, the image prompted me to consider how the two theories offer an intriguing indication of how scholars contend with the theoretical limits of their times. The nature of their response changes from era to era, yet in any epoch thinkers must eventually drop a conjectural marker at the edge of the known territory and gesture at what may lie beyond—Leibniz points to God, whereas contemporary physicists indicate the horizons of quantum cosmology. And from there, the work of advancing into these murky zones continues.

If you’re already familiar with 17th-century philosophy, Heretics! is a delightful refresher; if you’re not, it’s a fine introduction. In either event, if you’re up for a contemporary follow-up and a good hard think, philosopher Nick Bostrom’s 2014 work, Superintelligence—which holds a prominent place on the shelves of Elon Musk and Bill Gates—may do nicely. It considers a future when humans may find themselves coexisting with superintelligent artificial entities who could develop sentience. As Bostrom examines the very nature of being, you may notice some striking philosophical connections between the historical past and the speculative future, drawing together eras of reason and robots.

Dianne Timblin is book review editor for American Scientist.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.