This Article From Issue

September-October 2020

Volume 108, Number 5

Page 312

TREES. Bruce Albert, Archivio Architetto Cesare Leonardi, Lothar Baumgarten, Emanuele Coccia, Misha Gromov, Francis Hallé, Stefano Mancuso, Miroslav Radman, Verena Regehr, Ursula Regehr, and Abigail L. S. Swann. Edited by Pierre-Édouard Couton. 368 pp. Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2019. Distributed by Thames and Hudson. $60.

Everyone knows what a tree is. Definitions vary slightly, but no one looks at a tree and says, “What is that?” You may not know the species name, you may not know the common name, you may not know whether the tree is native or exotic or how it functions, but you know when you look at it that it is a tree.

From Trees

Whatever your concept of a tree may be, Trees—the magnificently illustrated catalog for an exhibition by that name presented at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris last year—is designed to greatly expand it. The tome in its entirety constitutes the broadest possible conceptual, scientific, philosophical, and pictorial compendium on the subject of trees. Indeed, it is so far-ranging and inclusive, and even dreamlike at times, that some parts of the book seem to have almost nothing to do with trees; in addition, tremendous effort is required to understand the book’s organization. But the book is wide in scope for a reason, and an exploration of its unusual perspective has its rewards.

Logistically, the book is a puzzle. The front matter one expects to find is absent; instead, the reader is immediately confronted with an odd poem about tree houses, in gigantic type. A “Contents” section follows, but it provides less guidance than one might wish. Four mystifying headings are listed: “The world begins with trees,” “Trees,” “The world is a crystal, the garden as a metaphor of the universe,” and “This is a blue planet, but it is a green world.” It takes some sleuthing to discover that the material under the “Trees” heading consists almost entirely of artwork and is actually divided into three parts, each of which follows one of the three sections labeled with the other headings.

From Trees

Fortunately, a brief foreword provided by the curators of the exhibit (Bruce Albert, Hervé Chandès, and Isabelle Gaudefroy) helps to clarify what the book is about and explains its conceptual basis. The curators point out that, compared with trees, which are “among the largest and oldest living organisms,” humans are latecomers to the planet and constitute far less of its organic matter. The curators hope that the exhibit and book will provide an increased understanding and appreciation of “these enigmatic giants” (our “great tutelary ancestors”), thereby enabling humans to “reconsider and retrieve” our place among all living things on planet Earth. In other words, the purpose of the book is to help us rediscover our appropriate (“modest”) place in the natural world, by guiding us on a “stroll” through a “forest of tree symbols.” Three narrative threads guide this journey: knowledge about trees (botany and plant biology), aesthetics of trees, and the current devastation of trees at the hands of humans.

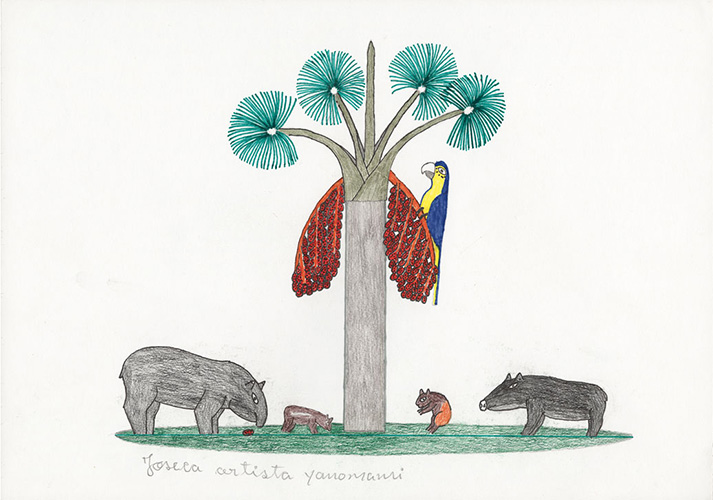

The book’s contributors, serving as the “ambassadors” of trees, are scientists, artists, architects, Indigenous peoples such as the Yanomami, philosophers, shamans, and thinkers. The contents include essays, quotes, interviews, narratives, Yanomami viewpoints, drawings, paintings, photographs, and descriptions of films and videos that were part of the exhibition. Among the book’s more than 400 illustrations—which vary greatly in style, content, and sophistication—every possible art medium is represented, including acrylic on paper, watercolor, pencil and felt-tip pen, oil on linen, monotype on paper, chromogenic print, black-and-white print, gelatin silver print, ink on paper, ink on tracing paper, and woodcuts. Trees is artfully exhaustive.

From Trees

Similarly reflective of the book’s sweeping scope are its essays. Contributions that will be of interest to a diverse audience include those dealing with the mathematics of tree structure, trees as an element of landscape architecture, phylogenetic trees, the evolution of plants, and the influence of trees on climate. I must admit, though, that I found the essay on plant intelligence by Stefano Mancuso confusing. An important shortcoming is that Mancuso’s comparison of perception and cognition in plants with that in animals is not well documented.

From Trees

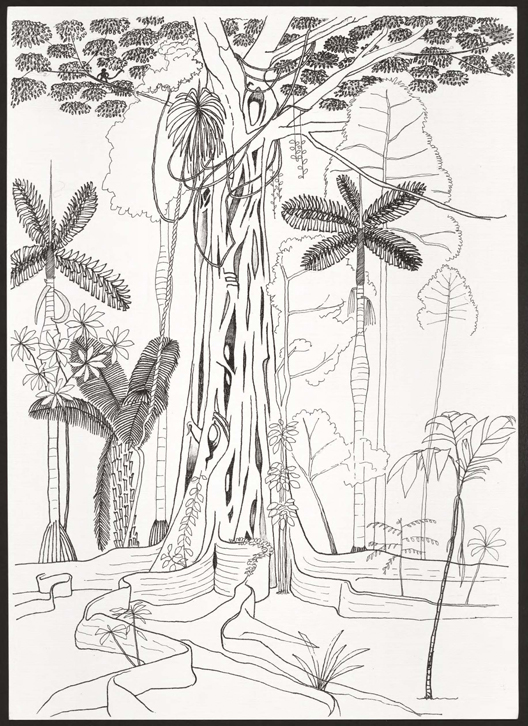

I am a botanist, and for me the scientific highlight of the book was a 16-page piece titled “A Life Drawing Trees,” which features an interview with the botanist and biologist Francis Hallé, a specialist in tropical rainforest ecology and the architecture of trees. The interview is liberally illustrated with drawings that he made in his field notebooks; these depict trees, parts of trees, and forest structure. Hallé has determined that each of the approximately 100,000 tree species alive today can be classified as having one of 24 possible architectural structures, based on how its branches are distributed and oriented and how its flowers are positioned. I first encountered these architectural models for trees as a college student, and I was particularly taken with the “Tomlinson” structure, because P. B. Tomlinson was a mentor to me when I was taking my first botany courses. I have observed Hallé’s architectural tree models in all of the tropical forests I have visited over the course of my own career. Thus it was exciting for me to see his drawings here and read his responses to the interviewer’s questions. An additional 20 pages of drawings by Hallé can be found later in the book.

From Trees

Scattered throughout Trees are sobering discussions of the destruction of forests and the decline in the number of tree species around the world. These bring us back to the disturbing realities of the 21st century. A “Timeline” at the end of the “blue planet, green world” section concludes the narrative portion of the book, even though another 70 pages of illustrations follow. This time line traces the history of Earth from its formation 4.6 billion years ago through the year 2015 (when scientists estimated that the total number of trees on the planet was 3 trillion). The 44 botanical milestones selected for the time line are astonishing in their breadth and detail: We learn, for instance, that the oldest known tree fossils date to 385 million years ago, and that sex in plants wasn’t discovered until 1694. Some explanation of how various events were selected for inclusion might have helped readers interpret the history portrayed. Nonetheless, the time line puts our current predicaments of climate change, biodiversity extinction, forest degradation, invasive species, social injustice, economic inequality, and even pandemics into very powerful perspective.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.