This Article From Issue

May-June 2001

Volume 89, Number 3

DOI: 10.1511/2001.22.0

The Ape and the Sushi Master: Cultural Reflections of a Primatologist. Frans de Waal. x + 433 pp. Basic Books, 2001. $26.

There must be a hundred books comparing ape and human behavior, so why read this one? Hasn't it all been said? Thankfully, no. This book needs to be read for at least three reasons: the unusual viewpoint of the author, the timely content and the fact that it is almost three books in one.

A Dutch primatologist and professor at Emory University, Frans de Waal was trained in classical ethology and has decades of experience with the behavior of our nearest relations in captivity. He spans divides: Europe-America, field-lab, monkey-ape, chimpanzee-bonobo. He is the author of five books, counting this one, and each has been better crafted than the last (like his role model, fellow Dutchman and Nobel Prize winner Nikolaas Tinbergen, he writes better English than do most native speakers). From Chimpanzee Politics (1982) onward, de Waal has been holding our primate cousins up for our viewing.

The Ape and the Sushi Master is about cultural primatology, an emerging field of inquiry. Actually, the book spans two uses of the phrase. One refers to human-nonhuman primate relations—how various human cultures have viewed monkeys as everything from vermin to gods; this might better be termed ethnoprimatology. The more interesting usage refers to the study of apes and monkeys behaving culturally; this is sociocultural primatology—the ethnography and ethnology of other species, rather than of other human cultures. This exciting enterprise now seems to be popping up everywhere (for example, in the January issue of Scientific American, Andrew Whiten and Christophe Boesch discuss the cultures of chimpanzees).

The three themes of The Ape and the Sushi Master (almost books in themselves) are how we see other animals, the nature of culture, and how we see ourselves. Each theme occupies about a third of the book. The first of the book's 11 chapters is a masterful prologue. Other chapters range from autobiographical musings, to natural history essays, to elegant treatises on topics such as morality, technology and teaching. There is a pervading Asiatic flavor, mirroring the parallel origins of primatology in Japan and the West. (The title alludes to the fact that the skill of making sushi is acquired through observation rather than formal instruction.)

From The Ape and the Sushi Master

In the book's first section, de Waal contrasts two powerful scientists whose lives were uncannily coincident, Kinji Imanishi in Japan and Konrad Lorenz in Austria and Germany. Each was tremendously influential but intellectually flawed. To get beyond their naive natural history, we need neo-Darwinian evolutionary theory. With it, we can combat what de Waal calls "anthrodenial" and be open to natural continua that include human beings.

The current challenge to this inclusive view of complex cognitive capacities is obvious: To what extent (if at all) are species other than ours cultural? (De Waal stays in the present and so dodges the sticky issues of whether extinct humanlike forms such as Neanderthals had culture.) Much of the debate starts with definition, and de Waal favors a broad one: Culture is nongenetic behavioral transmission. This casts the net wide enough to include many vertebrates, and perhaps even invertebrates. This will antagonize sociocultural anthropologists, who tend to attach more conditions, many of which are ultimately untestable—for example, the need for meaning.

De Waal finds animal culture in the use of stone tools to crack nuts and in the social customs of grooming, both shown by chimpanzees, but the examples he offers range far beyond the apes. As might be expected, he is strongest when relying on well-documented and replicated studies, and weakest when relying on anecdotes such as the story of Binti Jua (the zoo gorilla who "rescued" an injured child), which remains a story no matter how well it is told.

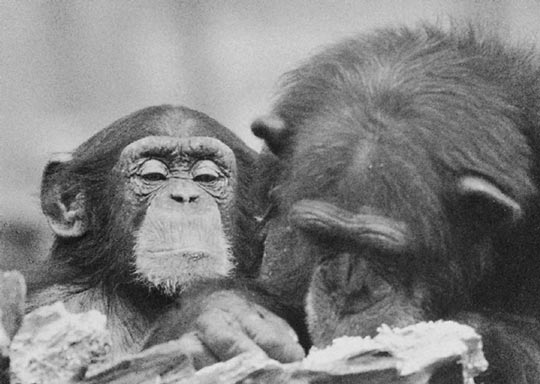

The book is targeted at the educated layperson. Superscripts refer to 23 pages of notes at the end, and for readers seeking to check sources, there is a bibliography of almost 300 references. There are 23 black-and-white photographs.

So, what can animals tell us about ourselves? De Waal hammers away at false dichotomies, some of which are familiar (Cartesian dualism) and some of which are topical: If other species have culture too, then what now is nature? It would seem to follow that humans are both cultural and natural at the same time. For example, the incest taboo has cultural and natural elements inextricably intertwined.

In checking the Web site of one online bookseller, I found de Waal's book listed among the cookbooks. This is understandable, given the title, but do not be misled. It is an intellectual feast!

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.