This Article From Issue

March-April 2008

Volume 96, Number 2

Page 156

DOI: 10.1511/2008.70.156

The Jewel House: Elizabethan London and the Scientific Revolution. Deborah E. Harkness. xviii + 349 pp. Yale University Press, 2007. $32.50.

Francis Bacon spent much of his life grumbling. He admitted that the Europeans of his day had surpassed the ancients in power and knowledge. Gunpowder, the compass and the printing press had enabled them to explore and conquer parts of the world whose existence had been unknown to the greatest Greek thinkers and to spread knowledge of these new realms to ordinary men and women. But in most schools and universities, the ancients still ruled. Students spent their time mastering Latin and Greek, learning the intricate rules of Aristotelian logic and debating the medical views of Galen and Avicenna. Most men still worshipped what Bacon called the "idols of the theatre": the existing systems and dogmas of the philosophers, which prevented them from seeing the world as it was. Authority, not experience, still reigned supreme in the sphere of learning.

True, Bacon dreamed of founding a new college that would work by different rules and attain operational knowledge—knowledge that yielded power over nature to those who possessed it. But he did not believe that such an institution existed in his own day. It is revealing that he set out his most detailed plan for the new college in a utopian novel, New Atlantis. Here he described an imaginary island, far from Europe, whose rulers devoted themselves to the study of nature. Its central institution, Salomon's House, was a center for collaborative scientific work, based on continual efforts to fathom nature directly and designed to further "the knowledge of causes, and secret motions of things; and the enlarging of the bounds of human empire, to the effecting of all things possible." For all the detail with which Bacon clothed his project, he saw it as a vision of the future, not a description of the present. At his most optimistic he hoped that divine intervention would realize it as part of the events foretold in the Book of Daniel.

Deborah Harkness devotes her elegant and erudite new book, The Jewel House, to showing that Bacon should not have been so pessimistic. In fact, she argues, Elizabethan London embodied many of his ideals, and the urban scientists who grasped these best also put them into practice more effectively than he himself did. Thanks to their imaginative collective efforts, London became the alembic in which a new mathematical and experimental culture crystallized. Harkness, the author of a major study of the Elizabethan mathematician and magus John Dee, is known for her ingenuity as a researcher and her historical empathy. These qualities enabled her to set Dee's pursuit of apparently abstract and mysterious forms of knowledge through dialogues with angels into a concrete, meticulously reconstructed historical context, in which it made considerable sense. The studies in which she recreated the "experimental household" that Jane Dee skillfully managed for her husband and the complex, impressive rituals that accompanied Dee's efforts to communicate with angels have become classics.

In The Jewel House, Harkness turns her skills on the city of London as a whole, with surprising and fascinating results. She began research, as she explains at the end of the book, by asking herself a new question: not what caused the scientific revolution but what the terms science and scientist meant in Bacon's London. Then she collected a vast range of sources, from printed books (on everything from pharmacology to mathematics) to scientific instruments and notebooks. Whatever she could learn about the nearly 1,800 men and women who produced these went into a relational database. And that in turn made it possible for her to do something that no historian before her has quite managed: to bring the extraordinary scientific communities that flourished in late 16th-century London back to quarrelsome, absorbing life.

Every chapter of The Jewel House charts the activities of a particular community. Harkness leads us through the streets of London, showing us, neighborhood by neighborhood, where the major forms of natural knowledge found homes. Apothecaries and naturalists settled in Lime Street, in what is now the City, where they created a dense network of shops, ateliers and gardens. Medical practitioners set up their tables where they could attract the punters and still hope to escape if officials noticed that they were practicing without a license—outside the Royal Exchange, for example, or at popular taverns. Mathematical instrument makers—such as the clock makers who kept church clocks in order—clustered in several parishes near St. Paul's, some of them dominated by immigrants and others by native craftsmen. The formerly wealthy merchant Clement Draper even managed to transform the King's Bench prison in Southwark, where he served time as a debtor, into a center of research and discussion. He and his visitors and fellow inmates investigated everything from purges and remedies for minor ailments to the philosopher's stone and the transmutation of metals. By the end of the book, Harkness has mapped London's scientific communities with astonishing precision.

When Harkness reconstructs these groups, moreover, she provides not traditional, static accounts of their theories, but dynamic analyses of their practices as these developed over time—often in the course of sharp debate. In many cases, as she makes clear, the naturalists and alchemists of Elizabethan London already practiced what Bacon saw as his central precept: that knowledge of nature had to rest not on authority but on experience. Critical thinkers, they not only collected vast amounts of information, but sorted and evaluated it with good sense and intellectual courage. As the physician and naturalist Thomas Moffett pondered the fossils that he had seen and the theories offered to explain their existence, he wrote, "at last I found that our Ancestors were here and there most foully deceived, and I ascribe more to my eyes and the eyes of [Thomas] Penny than to all their words." The lawyer and virtuoso Hugh Plat—who treated the claims of the great John Dee with informed skepticism—agreed: The best information came, in his view, not from books but from "the infallible grounds of practice."

True, not all the enterprises that Elizabethan projectors set in motion were unequivocal successes. Efforts by barber-surgeons like William Clowes to show in print that the Paracelsian healers who competed with them for patients were an uninformed rabble did help to establish the surgeons' authority. But no pamphlet series, however sharply written, could clear all the empirics, midwives and other unlicensed practitioners from the streets. Some of what Harkness calls the projects of Elizabethan Big Science—the companies that formed to mine or refine precious metals, for example, using the services of metallurgists and alchemists alike, in a blaze of hype reminiscent of the dot-com bubble—ended in controversy or even in disaster.

Yet the mathematical writers and instrument makers—as Harkness shows, drawing on a rich historiography—transformed the skills and interests of large sections of the British elite. The naturalists of Lime Street won the respect of the greatest authorities in the field across Europe. Above all, Clement Draper and Hugh Plat, the two forgotten virtuosi whose notebooks Harkness has reassembled through feats of detective work, emerge as passionate, informed and intelligent students of nature. They combined systematic and critical reading of contemporary texts with the collection of empirical data, and the dozens of anecdotes they collected show that they had many equally devoted and unjustly forgotten companions in inquiry.

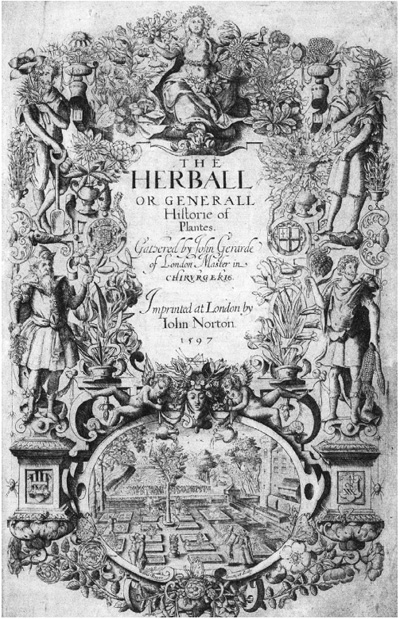

In one crucial respect, Harkness argues, many of the London scientists differed from the later, credit-hungry scientists of the 17th century. They saw themselves less as individuals out to secure fame through specialized study of particular aspects of nature than as members of larger textual communities, bent on exchanging and compiling information in manuscript letters and notebooks. The naturalists of Lime Street, for example, assembled better and more precise data about English plants than those that John Gerard managed to publish in his famous Herball—but they continued to prefer other ways to disseminate knowledge, such as the correspondence that linked them to the whole European Republic of Letters. The passages in which Harkness analyzes the Londoners' practices of note-taking and communication are among the most novel and informative in this fine book. She shows that they, like Bacon, adopted the textual information-processing methods of humanist scholarship to radically new ends.

Harkness believes that the City's scientists were both more scrupulous and more selfless than Bacon. In her version, Bacon used his manifestos to appropriate the credit that they deserved for designing a new and critical scientific community—one, moreover, that they actually brought into being. Here Harkness goes a little further than the evidence can carry her. Bacon had more respect for craft knowledge than she admits. More important, many of the substantive innovations in 17th-century scientific practice were in fact the work of egotistical men desperate to establish their own priority—men who broke with the collective mores she describes and created a new system of rewards, partly inspired by Bacon, for individuals who made scientific discoveries. Modern science could hardly have come into existence if all of its practitioners had been so unselfish as Draper and Plat.

Deborah Harkness has not quite proved that Salomon's House already existed in the London of Bacon's day. But she has charted the local and cosmopolitan worlds of science in Elizabethan London with a learning, precision and intelligence that compel admiration. Like the instrument makers who nested near St. Paul's, moreover, she has crafted a shiny, complex and effective new analytical mechanism—one that may well transform the practices of historians of early modern science, if others can muster the courage and energy to follow her example and analyze in similar depth and detail the scientific worlds of Florence, Nuremberg, Antwerp and Paris.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.