This Article From Issue

September-October 2004

Volume 92, Number 5

DOI: 10.1511/2004.49.0

Primate Psychology. Edited by Dario Maestripieri. xii + 619 pp. Harvard University Press, 2004. $65.

The history of the psychological study of primates begins with Charles Darwin—who was, among other things, a comparative psychologist. In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Darwin examined and compared the facial expressions of nonhuman and human primates, using zoo animals and his son William Erasmus as his research subjects. Indeed, in The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871), Darwin argued for a psychological and behavioral continuity between humans and animals, stating that "the difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind."

In the essay that introduces Primate Psychology, editor Dario Maestripieri notes that Darwin’s work, in turn, influenced the research of eminent psychologists in the first half of the 20th century. For example, Wolfgang Köhler looked for "insight" in chimpanzees as they worked to overcome obstacles to obtaining food. Robert Yerkes examined spatial cognition and social behavior in captive primates at the laboratory now named after him. And in the 1950s Harry Harlow investigated infant maternal attachment in captive rhesus monkeys.

One might expect that, given this auspicious start, modern–day psychology would be a field in which there is frequent dialogue and collaboration between researchers in the nonhuman primate laboratory and those across the hall who are studying human beings. But Maestripieri, who is an associate professor of human development, psychology and evolutionary biology at the University of Chicago, suggests that although psychologists have made progress in this direction, they need to be pushed further. In the 1970s, primate behavior as an area of study within the field of psychology was, for a time, sidelined, as advances in neuroscience led researchers to focus instead on the study of brain anatomy. And why examine neural pathways in primates when less expensive animals could be used to model the human mind? Additionally, Maestripieri submits that the absence of a strong theoretical focus—coupled with questionable methodological rigor—led to the perception that the psychology of nonhuman primates was not a "hard" science. Indeed, the 1980s and early 1990s were particularly rough, as funding continued to decline. Although some laboratories were still quite proficient, it was generally difficult for students from nonhuman–primate labs to succeed in the academic job market.

From Primate Psychology

However, as the research presented in Primate Psychology attests, times have changed. Maestripieri credits a resurgence of interest in nonhuman–primate behavior and cognition to various factors within psychology and related fields, including the emphasis on mind–body interactions and the increasing attention paid to the evolutionary origins of human cognition.

Why should we have an integrated nonhuman/human primate psychology? Although Maestripieri is not the first to answer this question, he does so convincingly. He points out that many psychologists today recognize that the human brain, like other organs, has undergone selective pressure, allowing our distant forebears to adapt to their surroundings, thus ensuring their survival and reproduction. A considerable number of these adaptations can likely be found in the shared ancestors of modern human and nonhuman primates. Even though we have drastically changed our environment through modern technological advances, we still face a social milieu similar to that of our early ancestors, one in which we must cooperate, compete, attain food and access mates. Thus we can be expected to share with nonhuman primates some of the adapted traits for succeeding within those spheres; and it would be equally informative to discover that we differ in significant ways. An inclusive primate psychology would provide a richer understanding of both the human and nonhuman mind, one in which the proximate causes and evolutionary adaptive value of mental processes are considered.

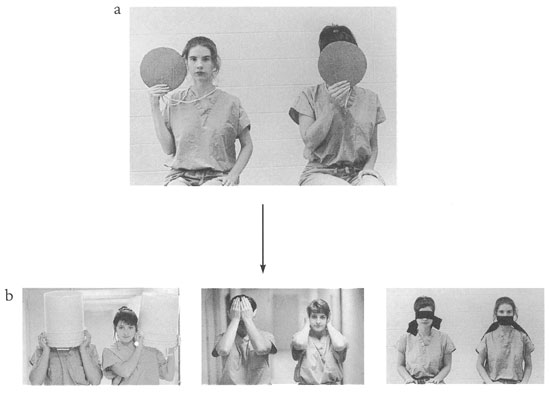

The book contains 15 additional chapters by various investigators, most of which review and discuss research on behavior and cognition in both people and nonhuman primates. J. Dee Higley holds forth on the neurological underpinnings of aggression, such as levels of serotonin, cholesterol and testosterone, and Peter Judge covers conflict resolution. Kim Wallen and colleagues discuss the social and hormonal aspects of sexual behavior. Maestripieri, Lynn Fairbanks and James Roney detail current research in attachment, parenting and affiliation. In a chapter on cognitive development, Jesse Bering and Daniel Povinelli discuss how chimpanzees and children differ in their ability to make inferences about things that cannot be directly observed, such as emotions, intentions and gravity. Josep Call and Michael Tomasello sum up what is known about the social insights of chimpanzees and what they do and don’t understand about the mental states of others. Four chapters cover various aspects of communication: nonvocal signals (Lisa Parr and Maestripieri), vocal yet nonlinguistic calls (Michael Owren and colleagues), the acquisition of language in nonhuman primates (Duane Rumbaugh and colleagues), and the relation between brain asymmetries and the evolution of language (William Hopkins and colleagues). Samuel Gosling and associates discuss personality research as applied to nonhuman primates, and Filippo Aureli and Andrew Whiten examine emotions and behavioral flexibility. Finally, Alfonso Troisi explores diagnostic criteria for psychopathology across primate species, including humans.

There is little to criticize in this book. I especially recommend Maestripieri’s excellent introduction, briefly summarized above, to students and established researchers alike. The chapters that follow focus on rich empirical findings in multiple areas of research, each of which deserves its own specialized review. Curiously absent, however, is the topic of numerical cognition, an area of study in which researchers have recently demonstrated the success that can come from collaboration and dialogue between those studying human participants and those studying nonhuman primates. Yet overall, the topics that are covered in this book provide a good background for those interested in studying the primary literature.

A lingering concern remains, though. One of Maestripieri’s intended goals in Primate Psychology is to "encourage communication between students of primate and human behavior." Surely the book will not impede progress in this regard. It will likely promote discussion and may have great effect on readers who do research with human subjects. But given the title and the close–up photograph of a gorilla’s face on the dust jacket, the book is more likely to come to the attention of those already studying nonhuman primates, which means that Maestripieri will be largely preaching to the choir. To fully achieve the goal of fostering better communication between the two camps, then, the onus is on those of us in the choir to sing louder and to keep on producing the type of rigorous, theory–driven science reported in this book.—Valerie Kuhlmeier, Psychology, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.