Electric Stars

By David Schneider

What accounts for the enigmatic x-ray pulses of V407 Vul?

What accounts for the enigmatic x-ray pulses of V407 Vul?

DOI: 10.1511/2002.27.0

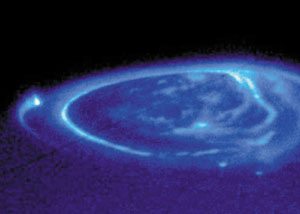

In 1955, radio astronomers from the Carnegie Institution of Washington uncovered an enigmatic source of static coming from the planet Jupiter. Later, other astronomers linked the noise to Jupiter's moon Io, which acts like the coiled armature in an electric generator: As it moves through Jupiter's strong magnetic field, the satellite produces electric currents. These currents in turn power the radio transmissions and produce ultraviolet light when they strike Jupiter's atmosphere. Now Kinwah Wu of University College London and his colleagues believe they may have found a star system powered by the very same mechanism.

NASA / ESA and John Clarke

The system, called V407 Vul or, alternatively, RX J1914, was discovered during a routine x-ray survey of the sky. What is strange about V407 Vul is that its x rays oscillate with an extraordinarily short period—under 10 minutes. Such rapid-fire pulsations are normally taken as a signature for a "polar," a highly magnetic white dwarf star that pulls material from a nearby companion. This material is channeled along magnetic field lines into the polar regions of the receiving star.

In 1998, Mark Cropper, one of Wu's colleagues in London, led an effort to study this x-ray source, and his team identified its optical counterpart, which showed the telltale 10-minute oscillation. Strangely, they discovered, the peaks at optical (and infrared) wavelengths come when the x rays are turned off, and the troughs come when the x rays are at their strongest. Also, it lacks the signature of a highly magnetic white dwarf that is accreting material: a spectrum with helium emission lines and light that is optically polarized. These various observations—and non-observations—were "quite confusing at first," according to Cropper, who says that for two years he, Wu and Gavin Ramsay (another member of his team) "were thinking, 'What on Earth could explain this?'" Nothing, of course. But then Wu suggested that something on Jupiter might.

Just as the currents that Io produces cause bright spots on Jupiter, the currents created by the orbital motion of the nonmagnetic member of this binary star system could easily light up its partner. Doing the appropriate calculations, Wu realized that this mechanism can release huge amounts of energy. "The power can be easily brighter than the sun," says Wu, "even 1,000 times brighter." The 10-minute x-ray pulses of V407 Vul are thus explained by the electrically heated spot or spots on one side of the star swinging into and out of view. The optical oscillations likely arise when the x rays strike the inner face of the other star, heating it enough to give off light. That inner face is most visible to us when the x-ray spot is hidden, and vice versa.

Not all astronomers agree with Wu's idea, which was published in March in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. One disbeliever is Tom Marsh of the University of Southampton, who with colleague Danny Steeghs presented a competing model in the very same issue of that journal. According to them, V407 Vul is indeed sending material from one star to the other, which they call "a direct impact accretor." Instead of swirling around and enveloping the receiving star in a diffuse disk, the material can, according to their report, "plough straight into the accretor even in the absence of the magnetic field."

As with Wu's conception, the source of x rays in this model is confined to one side of the star. The accompanying optical oscillations might come from the heated face of the donor star (as Wu and his colleagues surmise), or they may emanate from the star that is receiving material. Like a figure skater bringing in his arms, this star presumably spins more and more rapidly as it pulls mass inward. And if it rotates faster than the orbital period of its companion, the spot heated by the impact of material moves. Real estate downstream of the point of impact will remain anomalously hot for a time, accounting, perhaps, for the optical emissions.

So who's right? Tod E. Strohmayer, an astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, has recently weighed in with what may be the key to deciding. Strohmayer studied the timing of the x-ray pulses in greater detail and found that the orbital period appears to be slowly decreasing. Strohmayer sees his work as an indication that Marsh and Steeghs must be wrong, because the accretion of material onto one white dwarf from another would lead to a widening of the orbit and thus a gradual increase in orbital period. Strohmayer's results are, however, consistent with Wu's model, which predicts that the orbit will decay slowly over time, shortening the orbital period.

Strohmayer is somewhat tentative, because magnetic effects of the donor star could complicate the picture and because the donor star might not be a white dwarf, as the short orbital period suggests and as Marsh and Steeghs postulate. Strohmayer even allows that the star may be a polar after all, in which case the pulses must reflect the spin of the receiving star, not the orbital period of the system.

With many questions left to answer, V407 Vul will probably continue to draw the attention of astronomers who study interacting white dwarf stars. But it may not be at center stage. Gian Luca Israel of the Osservatorio Astronimico di Roma and colleagues have recently concluded that RX J0806, another pulsed x-ray source originally thought to be a polar, may in fact be a white dwarf binary, and it has an even shorter period—just over five minutes. In the time it has taken you to read this story, those two stars may have fully circled each other.—David Schneider

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.