Alien Life Is No Joke

By Adam Frank

Not long ago, the search for extraterrestrials was routinely dismissed as laughable nonsense. Today, it is serious and scientific.

Not long ago, the search for extraterrestrials was routinely dismissed as laughable nonsense. Today, it is serious and scientific.

Suddenly, everyone is talking about aliens. After decades on the cultural margins, the question of life in the universe beyond Earth is having its day in the Sun. The next proposed flagship space telescope, the Habitable Worlds Explorer, will be tuned to search for signatures of alien life on alien planets, and NASA has a robust, well-funded program in astrobiology. Meanwhile, from breathless newspaper articles about unexplained navy pilot sightings to U.S. congressional testimony with wild claims of government programs hiding crashed saucers, UFOs (unidentified flying objects) and UAPs (unidentified anomalous phenomena) seem to be making their own journey from the fringes.

What are we to make of these twin movements, the scientific search for life on one hand, and the endlessly murky waters of UFO and UAP claims on the other? Looking at history shows that these two very different approaches to the question of extraterrestrial life are, in fact, linked, but not in a good way. For decades, scientists wanting to think seriously about life in the universe faced what’s been called the “giggle factor,” which was directly related to UFOs and their association with fringe culture. More than once, the giggle factor came close to killing off the field known as SETI (the search for extraterrestrial intelligence). Now, with new discoveries and technologies making astrobiology a mainstream frontier of astrophysics, understanding this history has become important for anyone trying to understand what comes next. But for me, as a researcher in technosignatures—a new approach to SETI, seeking signs of advanced alien technology—getting past the giggle factor poses an existential challenge.

NASA-JSC

I am the principal investigator of NASA’s first-ever grant to study signatures of intelligent life from distant exoplanets. Taking on that role has been the culmination of a lifetime fascination with the question of life in the universe, a fascination that formed when I was a kid in the 1970s, drinking deep from the well of science fiction novels, UFO documentaries, and Star Trek reruns. As a teenager reading works both by astronomer Carl Sagan and by pseudoscientist Erich von Däniken, I had to figure out how to separate the wheat from the chaff. This process served as a kind of training ground for dealing with the questions that my colleagues and I are now facing about proper standards of evidence in astrobiology. It’s also why, as a public-facing scientist, I must work to understand how people not trained in science approach questions surrounding UFOs and aliens. That is what drove me, writing a recent popular-level account of astrobiology’s frontiers called The Little Book of Aliens (2023), to look hard into the entangled history of UFOs, the scientific search for life beyond Earth, and the all-important question of standards of evidence.

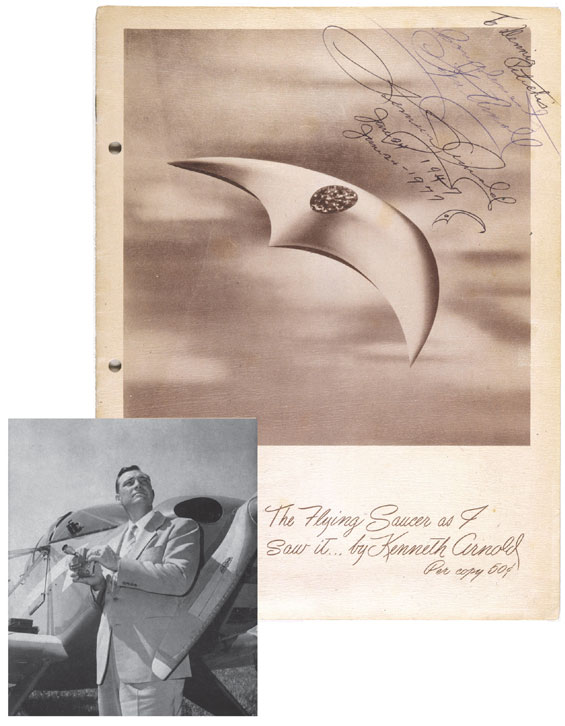

The question of what constitutes evidence for an extraordinary claim comes into play in the very first major UFO story. It was June 24, 1947, a good day for flying in the Pacific Northwest. The skies were clear and bright over Mineral, Washington. It was the middle of the day as the amateur pilot Kenneth Arnold found himself navigating his small single-engine plane past the towering peak of Mount Rainier toward an air show in Oregon. But he’d heard that a U.S. Marine Corps transport plane had gone missing, and a reward was being offered for anyone who found its wreckage. Arnold decided to make a few circuits and have a look. He didn’t know it at the time, but he was flying straight into UFO history.

As Arnold surveyed the terrain below him, he saw a flash of light with a blue tinge. A DC-4 was flying off in the distance, but there were no flashing lights coming from it. Then the flashes appeared again. This time, he saw exactly where the flashes were coming from: nine objects flying in a diagonal formation, which Arnold described as “like the tail of a Chinese kite.” Arnold watched as the objects banked and turned in ways that made him think he was watching some kind of advanced military aircraft, until they finally disappeared. The entire incident didn’t last long, but it left Arnold with “an eerie feeling.” After landing to refuel, he shared his story with friends at the airfield. What happened next would echo through history, shaping everything we think about UFOs and their connection to aliens from outer space.

Arnold’s tale spread quickly, and reporters from the East Oregonian asked him to come in and give more details. To the reporters, Arnold seemed like a credible witness and a careful observer. Laying out the timeline of what he saw, Arnold described both the craft and their motions. Exactly what happened next remains controversial, but when Arnold described the objects as moving like “a saucer if you skip it across the water” he triggered a chain of events leading to one of the most outrageous misquotes in the history of journalism.

The story in the East Oregonian, a small paper, ran with the words “saucer-like aircraft.” But when the Associated Press picked up the story, the description got even more garbled. What Arnold said he’d seen were flying craft shaped like a crescent with “wings” that swept back in an arc. Somehow, the Associated Press wire story misinterpreted Arnold’s description, leading the Chicago Sun to run a story with a spectacular front-page headline: “Supersonic Flying Saucers Sighted by Idaho Pilot.”

The Chicago Sun piece triggered an avalanche. Within six months, the flying saucer story ran in more than 140 newspapers across the United States. Even more remarkable, an epidemic of flying saucer sightings began to sweep the nation. By the end of summer in 1947, “flying saucers” were officially a thing.

Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

One of the most important lessons I learned from the Arnold affair is the power of a story. Arnold saw the first flying saucer, and his sighting begins a critical thread in the public’s willingness to go along on evidence-free rides of thinking about aliens and UFOs. It marked the point when the idea of technologically advanced, interstellar life here on Earth right now entered the public consciousness as a major phenomenon. But almost as quickly as UFOs appeared, so did a UFO culture that tilted toward the paranoid, marked by a willingness to take anything as evidence. Of course, one could find many individuals taking an interest in UFOs while keeping their skeptical sensibilities, who just genuinely wanted to know what was going on. But, as a cultural phenomenon, public discussion of UFOs would come to be dominated by questionable evidence, conspiracy theories, and outright hoaxes.

The Roswell affair, which took place just a few weeks after the Arnold sighting, embodies the most questionable evidence axis of UFO culture. The case involved a rancher in Roswell, New Mexico, who found some debris made of sticks, wire, and foil on his land. A short initial hubbub ensued, during which the local sheriff contacted a nearby army base, which in turn sent intelligence officer Major Jesse Marcel to investigate. A story in the local paper reported the discovery of a flying saucer (what else?), but that claim was walked back the next day. The official investigation determined that the supposed UFO was a crashed weather balloon.

The brief affair was then forgotten for 31 years, until Marcel changed his story. He went on a press tour claiming that the weather balloon was a cover-up, and that the crash was in fact an extraterrestrial spaceship. Marcel’s account sparked renewed interest in the Roswell story, which was resurrected in a series of bestselling books and TV “documentaries.” Each retelling added more so-called witnesses and more details, including a mortician named Glenn Dennis, who had allegedly viewed the dead aliens. Some books said there were more saucers and more aliens, some dead and some not. Some even said alien bodies were viewed by none other than President Dwight Eisenhower.

What’s important about the Roswell story is how loose even the idea of evidence becomes. Anyone with a vague connection to the events and a story to tell gets added to the list of witnesses. New books pile on old books and theories multiply until even those claiming to be serious UFO researchers can’t sort out which version with how many saucers and bodies is the one they’re supposed to investigate; garden-variety enthusiasts are beyond confused.

Theories multiply until even those claiming to be serious UFO researchers can’t sort out which version to investigate; garden-variety enthusiasts are beyond confused.

Although this craze might have seemed amusing to those on the sidelines at the time, it established a pattern of “anything goes” in the public’s perception of UFOs. This stigma became attached to SETI and has persisted for decades, creating an obstacle to researchers who want to approach the subject with a sincerity and scientific rigor.

That loose relationship between extraordinary claims and the evidence for such claims also had a profound effect on me as a teenager interested in astronomy and the possibility of extraterrestrial life.

At the time, I was reading both hard science books and speculative works about UFO-related topics. For a while, I’d become enamored of von Däniken’s book Chariots of the Gods? (1968) and its claims that many archaeological mysteries could best be explained by ancient aliens who had once come to visit Earth. That time ended when, one evening, I chanced upon a PBS documentary called The Case of the Ancient Astronauts (1977). It presented interviews with scientists who had spent their lives studying the subjects of von Däniken’s ancient alien speculations. The simplicity with which hard-won archaeological evidence trumped von Däniken’s claims left me both angry (I felt duped by his book) and exhilarated. The establishment of proper standards for what counts as evidence is what set the archaeologists apart from von Däniken’s wishful fantasies. The experience of that stark difference put an end to my interest in UFOs and visiting aliens of any historical epoch.

If the outlandish claims of alien speculators hadn’t made me so angry, they might have made me laugh—and it’s that giggle factor that has been so harmful to the establishment of the true scientific study of astrobiology that I work in now. When it comes to SETI, at least, UFOs made the nascent field an easy target for scorn.

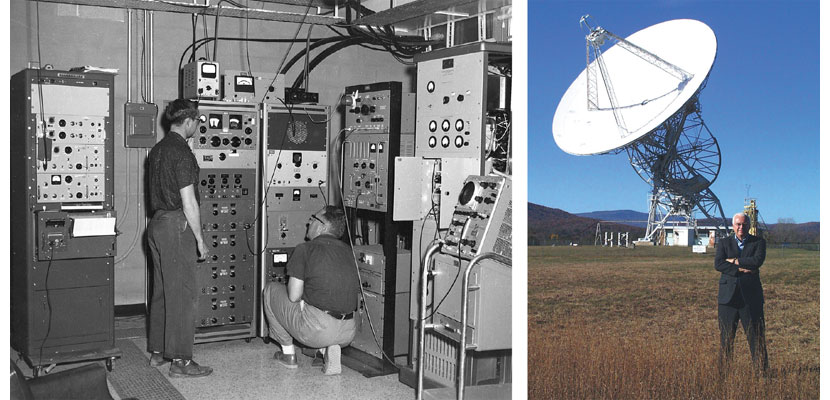

The first true SETI project occurred in 1960, when a young astronomer named Frank Drake used a radio telescope to search for “non-natural” signals from two Sunlike stars. (See “On the Hunt for Another Earth,” July–August 2023.) Drake’s search for intelligent life that could build technologies such as radio transmitters was the first true astrobiological experiment ever attempted. Drake’s effort marks the starting point for modern astrobiology, because his search was the first to take the critical idea of standards of evidence seriously. In the design and application of his experiment, Drake and his colleagues paid close attention to questions of signals, noise, and, most of all, false positives. They understood that they could be fooled into thinking they’d made a discovery by the data they gathered, and they attempted to prepare and protect themselves from that possibility. Drake’s SETI project and those that followed always attracted enormous popular attention. But building the field into a coherent, sustained scientific enterprise proved difficult, and it is here that UFOs got in the way.

In SETI’s heady first decades, a number of government science agencies had a healthy interest in the search for life, intelligent or otherwise. In 1961, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences hosted an Interstellar Communications meeting at which was born the Drake equation for estimating the number of communicative extraterrestrial civilizations in the Milky Way.

Green Bank Observatory / Flickr / CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0

By the 1970s, NASA was keen to go microbe hunting on the other planets in our Solar System. They invested billions of dollars in the Viking Project, which in 1976 became the first U.S. mission to successfully land spacecrafts on Mars. There was even consideration of Project Cyclops, a huge array of more than 1,000 radio telescopes sensitive enough to find unprecedentedly faint signals of intelligent life among the stars.

In all these projects, the scientists involved had to face the challenging task of understanding how to gather and evaluate evidence while simultaneously facing profound uncertainties concerning the target of that evidence. Researchers were well aware that, although we must begin with life as we know it (that is, life on Earth), nature might have other ideas. The creation of life originating on a different world could follow entirely different trajectories than how life evolved on Earth. Though the field was in its infancy, astrobiology researchers made slow but steady progress in mapping out how to rigorously gather and evaluate data that would be relevant to the very open question of how life beyond our world might make its appearance.

But then the question of UFOs entered the political sphere.

William Proxmire was a U.S. senator from Wisconsin who liked to think of himself as a crusader against profligate government spending. Beginning in 1975, he took it upon himself to bestow his monthly Golden Fleece Award on anything he considered a waste of U.S. tax dollars. Since the science projects he derided received only meager amounts of funding, Proxmire’s award was basically clever politics aimed at targets who couldn’t fight back. In 1978, NASA’s small portfolio of SETI funding fell into his crosshairs. That February, Proxmire gave NASA the Golden Fleece Award for a proposed 7-year, $14 million project to find intelligent life in outer space. And, being a powerful and influential senator, he convinced his colleagues to reject any new funding for SETI research. Proxmire relented only after Carl Sagan, by then a well-respected public scientist, intervened, meeting personally with the senator to discuss the issue. Although the ban on SETI funding was eventually lifted in 1983, the public political flogging of SETI as wasteful kookiness, with an implicit link to UFO kookiness, had begun.

NASA’s SETI funding remained minuscule in the post-Proxmire period, but it was still a target. In 1990, NASA tried to ramp up its SETI funding, from $4 million to $12 million, for a new search in the microwave region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Although the request was comparatively chump change in the federal budget, some politicians once again smelled blood. Making the link to UFOs explicit, Congressman Silvio Conte of Massachusetts tried to kill the funding, claiming, “We don’t need to spend $6 million this year to find evidence of these rascally creatures. We only need 75 cents to buy a tabloid at the local supermarket.”

The same game played out again a few years later. In 1993, those $12 million were finally allocated for the new search. Not wanting to attract more congressional attention, the project was stealthily called the High Resolution Microwave Survey. Unfortunately, Senator Richard Bryan from Nevada caught wind of the effort and saw it as an easy chance to make some headlines. He sponsored an amendment killing the project, announcing that it would be “the end of Martian hunting season at the taxpayer’s expense.” Of course, Bryan knew NASA wasn’t planning on turning their telescopes toward Mars, but who cared? His quip made for great copy and linked SETI to the cultural fringes where UFO enthusiasm lived, and the giggle factor killed the search for life in the universe again.

In the wake of these very public whippings, NASA learned the lesson that SETI was political poison. Although SETI scientists such as Drake and the unstoppable Jill Tarter did their best to demonstrate that the field lived within the necessary scientific standards of evidence, the damage was done. (See “First Person: Jill Tarter,” September–October 2018.) The agency did what it could in the decades that followed, but it became an accepted truth among researchers that federal support was going to be hard to come by. SETI scientists soldiered on, raising private money where they could. But, for all intents and purposes, the field was running on fumes. The giggle factor had won.

Choking off SETI funding had important consequences for the search for life in the universe because, basically, it meant there was no search for life in the universe. Using big telescopes costs big money. If there was no funding for SETI, then no telescope time would be granted for SETI. The political temperament that held sway for so long means our sky has effectively remained unexplored for signs of life. We simply have not looked.

In the early 1990s, it truly seemed that no one was very interested in the scientific possibilities of life beyond Earth. NASA’s 1976 Viking landers had conducted biology experiments on Mars that appeared to close the door on the red planet as a home for even microbial life. The trail for alien life of any kind seemed to have gone cold.

Then, in the mid-1990s, everything changed.

In 1995, scientists announced that they had discovered the first planet orbiting another Sunlike star—an exoplanet. After 2,500 years of arguing about the existence of other worlds, we’d finally proven that the planets in our Solar System were not unique. Soon, exoplanets were being discovered across the sky. Now, we know that pretty much every star you see at night hosts a family of worlds.

The next big change came the following year when scientists examined a chunk of Mars that had found its way to Antarctica. The meteorite (blown off the red planet by an ancient asteroid impact) appeared to contain signs of fossil life. Although that conclusion is no longer accepted, at the time it drove President Bill Clinton to direct NASA to go back to Mars and look for life. Between the discovery of exoplanets and the possibilities of ancient life on Mars, NASA got into astrobiology in a big way. Funding for new research opened up, allowing new and exciting ideas to be proposed and pursued.

Rather than hoping that an alien species has set up a beacon announcing their presence, we can now look directly at the planets where those civilizations might be just going about their business of “civilization-ing."

Remarkably, we are now also able to see exactly which exoplanets are in their star’s habitable zone, where liquid water (the key, we believe, for life) can exist. That means we know exactly where to look in our search for life. Exoplanet researchers have even developed a list of stars with planets, and which of those planets could potentially support life (something Drake could only have dreamed of). (See “What’s Next for Finding Other Earth-like Worlds?” September–October 2018.)

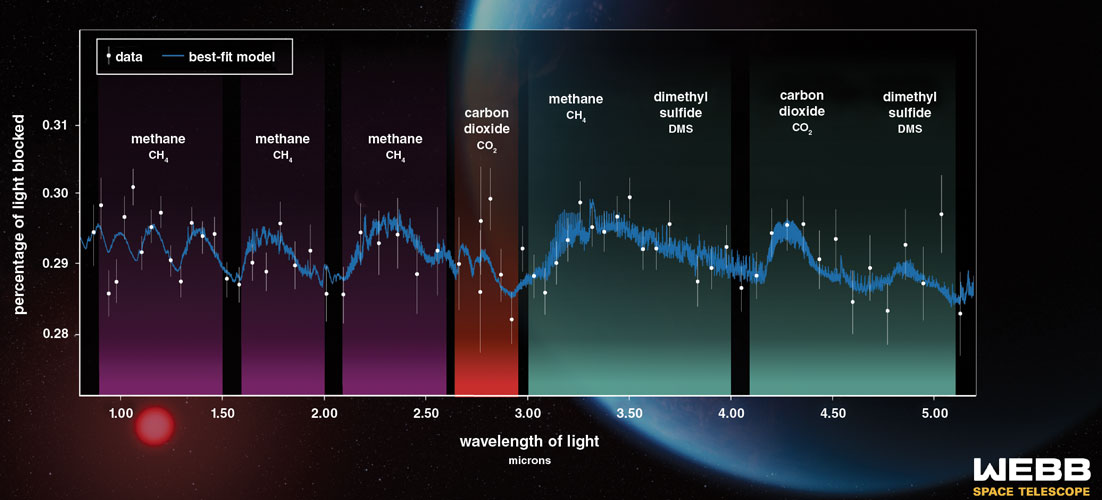

Even more remarkably, astronomers have learned how to look for alien life on alien worlds using starlight that has traversed the world’s atmosphere and then been absorbed by a variety of chemicals on the surface. (See “Direct Detection of Exoplanets,” September–October 2023.) This development means we can search for biosignatures—signatures of chemicals in a planet’s atmosphere that could indicate the presence of alien life.

Spectacular advances in the hunt for biosignatures have meant a profound refinement in the all-important standards of evidence. The earliest version of a biosignature was the presence of oxygen in an alien atmosphere. On Earth, oxygen is a significant atmospheric constituent only because photosynthetic organisms keep it there. Over the past decade, however, astronomers have discovered mechanisms through which planets without life might generate oxygen-rich air. This research was a crucial step in developing methods for evaluating false positives. Sophisticated statistical methods for evaluating false positives, as well as other challenges that astrobiological evidence will present, are now a robust part of biosignature science.

All these new discoveries and new methods are transforming what we think of as SETI. The emerging field of technosignatures embraces the “classic” efforts of SETI while taking the search for intelligent life into different forms and directions. (Some scientists still use SETI to refer to the field, and that’s OK. But for many, including myself, “technosignatures” correctly captures all that is changing in the field.) Rather than hoping that an alien species has set up a beacon announcing their presence (one premise of the first generation of SETI), we can now look directly at the planets where those civilizations might be just going about their business of “civilization-ing.” By searching for signatures of an alien society’s day-to-day activities, we’re building entirely new toolkits to find intelligent, civilization-building life.

In 2019, NASA awarded me and my colleagues the first grant to study atmospheric technosignatures. Although there are still only a handful of technosignature grants compared with those for biosignature studies, our grant was an indication that the giggle factor was waning. Since then, our group has worked hard to provide new examples of possible technosignatures, including some that might be searched for with the James Webb Space Telescope. We’ve also demonstrated that there is no reason to suppose that biosignatures will be more common than technosignatures. Since the exact same techniques are required to search for both bio- and technosignatures, there’s every reason to carry out both kinds of search at the same time.

NOIRLab/AURA/NSF/P. Marenfeld

And those standards of evidence developed for biosignature searches will be just as relevant for technosignature work. Our group, led by the astrophysicist Manasvi Lingam from the Florida Institute of Technology, recently published the first study attempting to lay out a framework for evaluating false positives in technosignatures. Although there is enormous work ahead of us, it is projects like these that will allow us to fully understand the confidence we can ascribe to any claim of an intelligent-life detection.

With the giggle factor receding for the scientific search for life, where does that leave UFOs and UAPs? There, the waters remain muddied. It is a good thing that pilots feel they can report sightings as a matter of air safety and national defense without fear of reprisal. And an open, transparent, and agnostic investigation of UAPs—evaluated with the same rigor as any other type of scientific evidence—could offer a master class in how science goes about its business of knowing rather than just believing.

Although we should let future studies lead us where they may, there is simply no evidence surrounding UFOs and UAPs that meets rigorous scientific standards today. In fact, at a public hearing held in May 2023, NASA’s UAP panel stated that only about 5 percent of reported sightings failed to find a reasonable explanation. Many of the remaining cases did not have enough data to even begin an attempt at identification. The sky is simply not awash in unexplained phenomena.

In the end, what matters is that, after thousands of years of arguing over opinions about life in the universe, our collective efforts have taken us to the point where we can finally begin a true scientific study of the question. It is significant that one of NASA’s top priorities is a space telescope called the Habitable Worlds Observatory. The name tells you all you need to know. We’re going all in on the search for life in the universe, because we finally have the capabilities to search for life in the universe. The giggle factor is finally history.

This article is adapted from a version previously published on Aeon, aeon.co.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.