This Article From Issue

September-October 2003

Volume 91, Number 5

DOI: 10.1511/2003.32.0

Wings of Madness: Alberto Santos-Dumont and the Invention of Flight. Paul Hoffman. xii + 369 pp. Theia, 2003. $24.95.

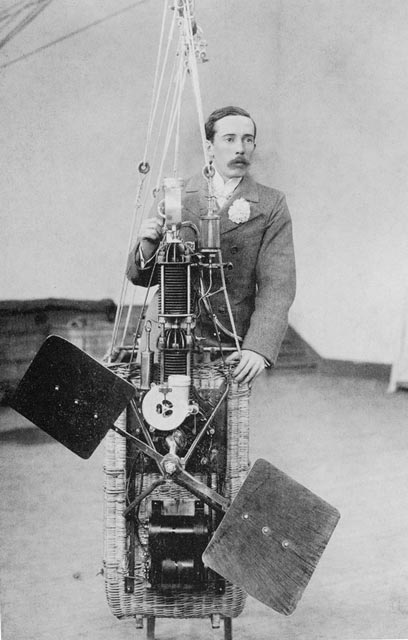

Alberto Santos-Dumont, born in 1873, was a genuine pioneer of aviation. A wealthy Brazilian, he lived much of the time in Paris, and most of his aeronautical achievements took place in France. He started with balloons and advanced to powered blimps. Then in 1906 in Europe, he made the first public airplane flight, in Bird of Prey, a plane he helped devise with a box kite at the front and an engine in the back. And finally in 1909 he produced the world's first sport plane, Demoiselle.

From Wings of Madness

Santos-Dumont was devoted to the principle that aircraft should be used only for nonmilitary purposes. As planes were turned into weapons in World War I, his despair at contributing to warfare was so intense that his physical and mental stability lessened, to the point where he sometimes required sanatorium stays. Back home in 1932, when he became aware that planes had bombed pro-democracy Brazilian insurgents in the then-simmering civil war, he hanged himself, although his official cause of death was listed as cardiac arrest.

In spite of his creative dedication and well-publicized successes, Santos-Dumont has been virtually ignored in aviation histories, most of which focus instead on the exploits of George Cayley, Otto Lilienthal, Orville and Wilbur Wright, and Glenn Curtiss. Nevertheless, Santos-Dumont's triumphs were spectacular, and they were appropriately appreciated by the public, especially in France and Brazil: After his famous 1906 flight (of 722 feet), for example, a crowd carried him up and down the boulevards of Paris for half a day. When he died, the town of Cabangu (his birthplace) changed its name to Santos-Dumont, a three-day truce was called in the Brazilian civil war, and combatants from both sides lined up together for miles to file past his open casket in São Paulo.

Paul Hoffman, past president of Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., and former editor in chief of Discover magazine, brings Santos-Dumont to the modern reader in the delightful history Wings of Madness. Hoffman researched the man extensively, finding hundreds of letters Santos-Dumont had written, as well as old magazine and newspaper articles about his exploits. However, Hoffman could not consult copies of Santos-Dumont's sketches and blueprints or of the congratulatory letters others sent to him. The reason: Although Santos-Dumont was horrified when Germany attacked his adopted country in World War I and was therefore planning to put himself at the service of the French military, his neighbors suspected him of spying for the Kaiser (by using his telescope to signal U-boats) and turned him in to the military police. They searched his home, found nothing and apologized—but immediately afterward, mortified at being suspected of treason, he set fire to his aeronautical documents.

Santos-Dumont's designs of free and powered balloons, buoyed usually with hydrogen or hot air, were always original, although not always successful. His first flight was in 1897. The next year he flew several hundred times in Brazil (his very small hydrogen balloon) and began development of a one-person cylindrical airship with a 3.5-horsepower motor (Santos-Dumont No. 1), which never flew particularly well. In 1899 he constructed a larger version, No. 3, which was lifted by lamp gas and made dozens of flights, including one around the Eiffel Tower and one that lasted a record 23 hours. Then, after some unsuccessful experiments, in 1901 and 1902 yet another of his one-person airships, No. 6, performed many feats, including winning the Deutsch prize for circling the Eiffel Tower and making repeated flights over the Mediterranean. In 1903 he flew everywhere in his tiny Baladeuse (airship No. 9) and permitted Aida de Acosta, an American debutante whom he had just met, to use it to become the first woman to fly solo. His balloon program ended with Baladeuse, although an airship did serve as an aerial tug in 1906 for one of his heavier-than-air craft. His ballooning/airship experience exceeded that of any other human, and his successes with those vehicles were enthusiastically applauded by the public in France and other countries.

From Wings of Madness.

When Santos-Dumont made several short flights in 1906 with Bird of Prey (a biplane with its horizontal stabilizer positioned in front, rather than affixed to the tail), he got as much feverish praise as for his balloon and airship programs. In 1908, however, Wilbur Wright, departing from the penchant he and his brother had for keeping their aircraft designs secret, conducted stabilized flight in France, once staying aloft for 2 hours 18 minutes. Except in Brazil, the public's enthusiasm ended for the shorter, marginal flights of Santos-Dumont's Bird of Prey. Nevertheless, his 1909 Demoiselle was the world's first sport plane. It set a speed record of 55.8 miles per hour and was widely copied in the United States and Europe.

Hoffman provides a history of Santos-Dumont's projects. In addition, he brings much interesting background to light. Santos-Dumont was truly unique—a wealthy social activist dedicated to modern technology. He was unusually small, standing 5'4" and weighing 100 lbs. Despite his shyness, he was talkative with close friends and was occasionally very friendly to others, especially those who held his developments in high regard. His clothing was immaculate. His good luck was well manifested by his many narrow escapes from danger in his aeronautical missions. He gave the prizes he won to his employees and the poor. He inspired many technical advances but was not himself mercenary: He believed his aerial innovations should be given to the world, and therefore he never applied for patents.

Santos-Dumont was once the most famous and revered man in France. In Brazil, where the secret flights of the Wrights are discounted, he is still considered the principal figure in early aviation. In 2000, Paul Hoffman visited a small museum at an air-force academy on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, where a life-size replica of Santos-Dumont's 1906 plane and a gold-plated sphere that contains his preserved heart are on display. A soldier there spoke to him of Santos-Dumont: "Why has the world forgotten him? And forgotten his message that the plane should not be used for destruction? . . . It is your mission to tell the world about Santos-Dumont. Do it for the glory of Brazil!"—Paul B. MacCready, AeroVironment, Inc., Monrovia, California

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.