A Tour of Geological Spacetime

By Philip Morrison

A whirlwind itinerary for the globe-trotting geologist

A whirlwind itinerary for the globe-trotting geologist

DOI: 10.1511/2004.46.120

A dozen or two well-celebrated travel destinations, from the chilly heights of Davos to the balmy beaches of Ipanema, are the jewels in a global tiara of enjoyable resorts, fashionable boutiques and high prices. Even vicarious travelers are familiar with the scintillating culture and unrivaled shopping that decorate such grand settings. These spots are far beyond the reach of most scratch planners of travel, but such indulgent playgrounds of an elite, this spacetime, is captured on many a screen and page, consumed by modest hopefuls, eager to take one trip soon, and less likely to shop for chic than for the prudence of maps, fine postcards, a few souvenirs and perhaps one big, beautiful book.

Yet these destinations are often mere artifice compared to the prime sites that proclaim the narrative of the Earth. What thoughtful voyager would not want to take in those instead? Here is a sketch for one such tour, which knits together visits to a few of the marvels of our planet's geologic past. Travelers can experience these glorious scenes first-hand—admittedly delayed through geological time—in a display of ancient wonders, some found quite close to home.

Upscale Rodeo Drive extends north from Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, proffering a glossy collection of high shopping en route to exclusive Bel Air. Rather improbably, just three miles eastward along the boulevard lies the first earth-study destination, the tar pits at La Brea. Two dozen acres of parkland adjoin the thronged street. Instead of green grass, natural pools of hot, slow-simmering asphalt occupy the preserve. That engulfing blackness rises out of the earth from as much as 30 feet down, and it has done so for the past 40,000 years. A handsome little museum there provides the visitor with some helpful perspective, including a revealing, century-old photo of the site, in which a smoky and nearly unpeopled plain extends north to the hilly horizon. Only natural oil seeps give texture to the flatland where half the city now stands.

The excavations at La Brea, some still underway, have yielded the fossilized bones of thousands of incautious creatures caught in these sticky traps: Saber-tooth cats, vultures, white-footed mice and voles in variety have all emerged from the depths of this awesome fly paper. Only 17 human bones have ever been found, those of a young woman, perhaps an anciently abandoned victim of the tar. Visitors can glimpse such Pleistocene dramas at this small, compelling, earthly museum.

Not all of the destinations on the tour have such tiny scale: You need to be able to take in the long view of some things too. The North American continent is an example. Many people have wandered enough to visit east and west ocean coasts, but even seasoned travelers may not realize that about halfway between the equator and the North Pole, clear signs of continental drift are visible. As one steadily follows the setting sun, the Oregon coast appears with little notice, because the landscape is so new that the boundary between earth and sea is still being negotiated. You can even watch the process in style: Restaurants perched on steep cliffs allow you to sip wine as huge wind-driven waves contest with boulders below. On the Atlantic side, so abrupt an approach to salt water is uncommon. There the coast is old and worn. As a result, travelers to the sea are more likely to cross long foreshores, ample beaches and wide estuaries.

North of Perth in Western Australia, the coastal Hamelin Pool hosts a layered shoal of colorful bacterial mats. Forming in brackish seawater, layer after layer of mats have left behind clusters of small, sedimentary columns. The dry, fossilized equivalent (with matching microbial content) lies close by on the same shore, marooned billions of years ago by a changing coastline.

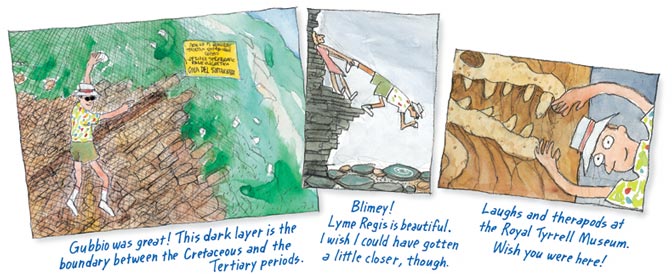

Tom Dunne

In Lyme Regis, a popular beach resort in England, erosion of the sea cliffs feeds the beach shingle with fossilized, tropical shells. These ancient, aquatic relics are common for miles along the maritime bluffs. People come to pick over the beach wrack for the coiled, weather-revealed shells. The site also yields the occasional fossilized sea dragon, creatures that are both large and ancient. The bones of such an ichthyosaur, recovered here by young Mary Anning sometime around 1810, constitute the first giant skeleton recognized in Britain. In more recent times, the remains of juveniles from related species have been discovered in the area.

The biggest dinosaur skeleton ever assembled is 74 feet long. Such huge fossils of herbivores and their grim-jawed predators are found around the globe. The Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada, has one of the biggest collections, owing to a nearby source: A few miles from the museum, the Red Deer River has incised a winding valley through green rolling farmlands, and it has revealed in the colorful canyon walls impressively large skeletons now on display at Tyrrell. Paleontologists believe that many more fossils await discovery in the area. A new find is always under excavation.

The remains from other Mesozoic sites, while not so large, are especially showy. In the Bavarian town of Solnhofen, a dozen miles from the Danube, residents have used the white, amazingly flat limestone slabs of their quarries for floors, walls and roofs since pre-Roman times. The demand for local stone increased dramatically when at the end of the 18th century, Alois Senefelder showed how to use the finely grained slabs for lithography, a technique for printing ink on paper using a flat, greased stone.

As a result of the demand for lithographic plates, much of the area was excavated, revealing a large number of very well preserved fossils. Our own book shelves hold one such heavy limestone block from Solnhofen that bears the impression of a large dragonfly, naturally cast at the plate surface. Such stones were useless to the early quarriers, although they would often take the specimens home as curiosities.

The Solnhofen site is rife with spectacular finds owing to its situation near the edge of the ancient Tethys Sea where salty, oxygen-starved lagoons often formed. (The fineness of the chalk powder at this site is so remarkable that it can have settled only in a ponded body of water long undisturbed even by tiny waves.) One hundred fifty million years ago, these pools were only kept wet by infrequent surges from shallow seas nearby. Evidence of many animals has been preserved in the even layers of sediment, including two complete specimens of Archeopteryx lithographica, the first bird, which sported reptilian teeth and a feathered body.

Other such special storehouses exist. The Messel Pit, near Darmstadt, sits amid a coal-veined wetland not very far from the Solenhofen lithographic source. The Messel site became a much-worked mine for oily black shale, then a large refuse pit. But the value of its fossil mammal collection far outweighs its worth as a dump. A parade of ancient horses from Messel, for example, makes very clear that fifty million years ago the time for mammals had come.

Another treasure of ancient life is in Rhynie, a rolling rural district in the Scottish Highlands, not far from Aberdeen. Rocky outcrops offering delicate plant fossils are widespread over that grassy landscape. Trapped within the chert, a vast array of Devonian plants are preserved in large numbers, appropriate companions to the living carpet covering the site today.

Whereas impeccable Gucci crafts stud the mercantile constellations, our star list offers instead the old Italian city of Gubbio in the Appenines. There posted on a main road are signs leading the interested visitor to a layered rock wall. You can put your finger carefully at the clay-filled centimeter or so between the latest of the chalky Cretaceous strata and the earliest of the Tertiary, when little mammals first found their way open to fortune. After the brief moment in geological history when this strip was laid down, no dinosaurs remained.

These aren't the only gems. The jewels of Earth history are littered everywhere and are easily found. Look for layered canyons or fresh-faced highway roadcuts. Seek craggy spires from Patagonia to the Alps, or wide flatlands where an uncertain river zigzags its lost way to the sea. Treasures await the curious, and any modest atlas will offer clues.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.