This Article From Issue

January-February 2011

Volume 99, Number 1

Page 70

DOI: 10.1511/2011.88.70

MOSQUITO EMPIRES: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620–1914. J. R. McNeill. xviii + 371 pp. Cambridge University Press, 2010. $94.99 cloth, $24.99 paper.

Mosquitoes live brief but busy lives feeding on nectar and plant sugars. The females must also find human or animal blood to feast on in order to produce eggs and continue the life cycle, so they live rather longer than the males—several weeks rather than several days. Frail though individual mosquitoes appear, historically they have shown an impressive propensity to travel. Sometimes they have been stowaways on ships traveling to other continents, carried aboard in water casks and drinking vessels. On arrival in new lands they have exploited the ecological changes—deforestation, canal building, rice cultivation, urban water storage and deficient drainage—brought about by their obliging human hosts. Despite occasional suspicions that mosquitoes were up to no good, most human observers before 1900 were remarkably unaware of the insects’ true role. They were inclined to regard mosquitoes as a nuisance—often a prodigious one—rather than the death-dealing menace they actually were. The creatures’ frailty belied their fatality.

As accomplished environmental historian J. R. McNeill brilliantly demonstrates in Mosquito Empires, for nearly 400 years the human history of the Americas, from the northern shores and interior plains of South America through the islands of the Caribbean to the southeastern corner of the present-day United States, was governed by the activities of “imperial mosquitoes”—both the Anopheles species that were the vector for malaria and more especially Aedes aegypti, which harbored lethal yellow fever virus. His central argument is that when Europeans first established themselves in the Americas in the 16th century, they had an epidemiological advantage in that the diseases they brought with them (such as smallpox, measles, mumps and whooping cough) caused devastation among indigenous populations. But in the 17th century, migrant mosquitoes such as Aedes aegypti were introduced to the Americas, largely through the mechanism of the transatlantic slave and sugar trade, with ships serving as “super-vectors, efficiently moving both mosquito and virus from port to port.” Once new diseases such as yellow fever made the crossing from West Africa, transported by mosquitoes or traveling in the blood of their victims, then the disease ecology of the Americas was profoundly transformed. Major demographic and environmental changes were also taking place—hundreds of thousands of slaves were imported, and forests were cut down for fuelwood used to boil sugar. The once benign Caribbean became a “giant sinkhole” of suffering humanity.

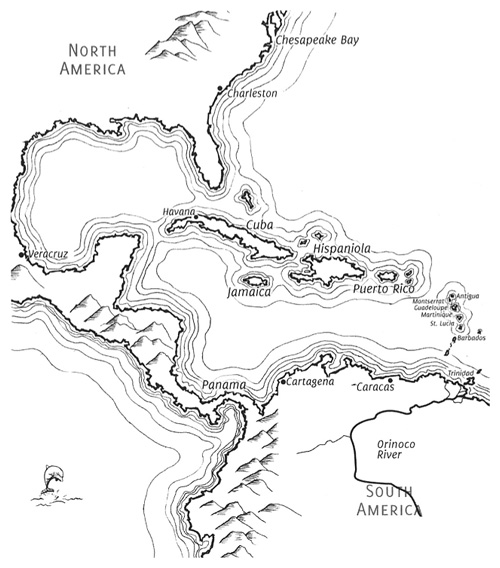

The broad lines of this epidemiological transformation are already well known, to medical historians at least. Where McNeill excels is in demonstrating, through a close reading of contemporary sources and of modern medical literature, how specific environmental changes in the Americas—especially the “ecological turbulence” caused by land clearance, plantation agriculture and urban expansion—created conditions in which immigrant diseases and their insect vectors flourished, and in which the differential immunity or resistance so central to this story began to operate. McNeill wisely eschews the overemphasis on race that has plagued many previous discussions of these issues, drawing attention instead to the formative role of specific environments (in Africa as well as the Caribbean) and of prior disease exposure. As he notes, by the late 17th century, individuals who had been born or had grown up in those areas of the “Greater Caribbean” (see map on facing page) in which malaria and, above all, yellow fever were rife likely either had an inherited immunity or had acquired protection through exposure to the diseases in childhood, when they were less often fatal. The epidemiological advantage now rested with the locals, whatever their racial composition, as opposed to those arriving unprotected from Europe or from relatively fever-free parts of the Americas. Many Europeans disembarked from ships only to go straight into their graves.

Worse still, McNeill reminds us, medicine was no solace to the sick: The medical treatments employed at the time, including copious bleeding, or venesection, only worsened the patient’s condition, just as confinement in a hospital stuffed with fever-sufferers was bound to hasten an already imminent death. McNeill presents compelling evidence for the overwhelming mortality—especially from yellow fever—that devastated invading forces during this period, rendering them unfit to fight or to hold their position once gained. Casualty rates as high as 80 percent or more were seen in some of the forces involved in the British assault on Cartagena in 1741 and the siege of Havana in 1762. The defending forces, however, were shielded by their immunity and survived relatively unscathed.

A further achievement in this compelling tale of vectors, viruses and victims is the subtle use of ecological insight to inform the political and military history of the region, without recourse to crude determinism. Like several other recent historians, McNeill draws upon scientific knowledge of the El Niño event and the wider ENSO (El Niño/Southern Oscillation) phenomenon to explain dramatic shifts in weather patterns and the proliferation of mosquito-friendly—and therefore disease-conducive—conditions. Through a series of deft case studies, he shows how political and military leaders unwittingly created situations in which the disease factor became decisive or shaped the strategic thinking of opposing armies.

Even though they were unable to identify the cause of epidemics or to reliably predict their occurrence, people widely recognized that a new “ecological-military order” had come into being. Thus the Spanish, entrenched across a large part of the Greater Caribbean by the mid-18th century, were able to defend their domains by building fortifications that would delay the English and French long enough for the rainy season to begin and the invaders to be incapacitated by disease. And in one of McNeill’s most edifying examples, the American rebels’ evasive tactics, aided by disease, made it impossible for the British to regain control of the Carolinas during the Revolutionary War. With an army debilitated by malaria and largely confined to the fever-prone coast, Cornwallis was forced to capitulate at Yorktown in 1781. McNeill wryly observes that the tiny female Anopheles quadrimaculatus, one of the 30 or so malaria-transmitting mosquito species, deserves to be ranked among the “founding mothers of the United States.”

It is the subtle but lucid manner in which McNeill explores the multistranded relationship between physical environment, insect agency and human decision making that makes Mosquito Empires such a persuasive piece of historical writing. Before the 1890s, generals and guerrillas appear to have had little idea, other than a vague notion of “climate,” as to what caused epidemic mortality. Wily defenders and “canny revolutionaries,” however, had a limited understanding of differential immunity and used it to great practical effect. More than that, McNeill is able, as few have done before him, to connect all these episodes, from the English conquest of Jamaica in the 1650s through the sieges of Cartagena and Havana, the disastrous Scottish and French settlement schemes in Panama and Guyana, the catastrophic Anglo-French interventions in St. Domingue, the wars of American independence and the final eclipse of Spanish power in 1898. He renders them into a cogent narrative, ending with the final dethroning by modern medical science of mosquito rule after 400 years of turbulent history.

This is a remarkable book for its scholarship, but it is also a very readable one. In relating insect-borne disease to the ebb and flow of human history, it shows how effectively science can be written into history.

David Arnold is Professor of Asian and Global History at the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom. He has written extensively on the history of modern India and on medical and environmental history, and is the author of several books, including The Tropics and the Traveling Gaze: India, Landscape, and Science 1800–1856 (University of Washington Press, 2006).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.