This Article From Issue

May-June 2012

Volume 100, Number 3

Page 257

DOI: 10.1511/2012.96.257

THE GLOBAL BIOPOLITICS OF THE IUD: How Science Constructs Contraceptive Users and Women’s Bodies. Chikako Takeshita. xvi + 238 pp. The MIT Press, 2011. $30.

Chikako Takeshita’s The Global Biopolitics of the IUD traces the scientific and political history of the intrauterine device (IUD) from the 1960s through today. This birth control device, Takeshita writes in this contribution to The MIT Press’s Inside Technology series, may have been employed to reinforce patriarchal ideals that deny women agency—but even in these cases, women have often converted it into an instrument of individual power, in part because the IUD can allow a woman to keep her birth control method hidden. The device thus has at times been associated with efforts to inflict control on the womb, but women also have used it as a method of exerting control in cultural or personal milieus that otherwise may not allow it. Given the current political climate, a book about how a “simple” piece of plastic both controls women and allows them control is timely.

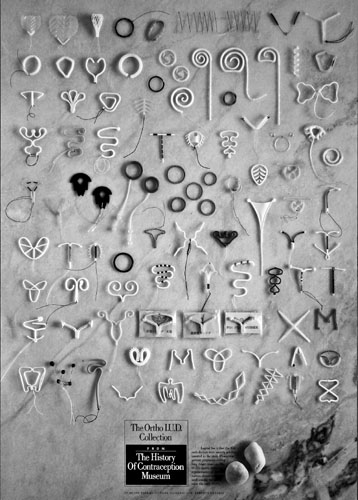

From The Global Biopolitics of the IUD.

Social context, Takeshita says, not only influences the design of IUDs themselves and how they are marketed and used, but also shapes the conduct of scientific work about them. She begins with the assumption that any such technology will involve “webs of state and nonstate investments” in the bodies, health, sexuality and reproduction of women. The medical researchers who have developed IUDs, along with the organizations that back them, she argues, grasp these varying interests and have made and marketed IUDs based on prevailing social climate, ultimately centering on the white, middle-class Western woman as a target user.

The IUD—whose mechanism of contraception was long unclear but which appears to work primarily by disrupting processes necessary for successful fertilization or by blocking attachment of fertilized eggs to the uterine wall—is thus also a political device, or, as Takeshita writes, a “politically versatile technology.” To make her point, she travels through modern IUD history from its beginning as “birth control for a nation” in the 1960s, when the device was first marketed for widespread use, to the present reemergence of the IUD. To aid in this explication, she introduces the term biopower, coined by social theorist and philosopher Michel Foucault to describe how societies seek control and regulation of the individual and collective bodies that make them up. The IUD stands out because, unlike other nonsurgical forms of birth control, it is imposable on a woman’s body, which removes control from the woman. Yet a woman can use it discreetly and over the long term, which gives the woman control.

This paradox of the IUD reflects its history, which Takeshita unfolds over the course of the book. Chapter 1 gives an overview of the various social, political and scientific stakeholders in the IUD, and the next four chapters show how the political and social ground around the device shifted even as its target—the uterus—remained the same. In chapter 2, Takeshita focuses on the IUD as a global population control device. The Population Council, a group formed in the United States in 1952 with the goal of promoting population control, first entered into active involvement in contraceptive development when, in the early 1960s, it began to fund research on IUD development. Takeshita notes that the Council’s president stated in 1969 that the Council favored “research on a mass involuntary method with individual reversibility’”—a stance that removes control from women. Over its five-decade modern existence, the IUD has morphed again and again—literally, politically and socially.

From The Global Biopolitics of the IUD.

The IUD as a physical object does not escape Takeshita’s notice. She describes in absorbing detail the very geometric approach male designers took to creating a device that would “occupy the uterus,” in the words of IUD researchers Michael Burnhill and Charles Birnberg, fully and continuously. The astonishing figures that accompany the text include a visual presentation of the staggering variety of IUDs that have been developed since the 1920s. In a section titled “Visualizing Uterine Occupation,” Takeshita presents a series of x-ray images of uteruses “occupied” by IUD devices. Scientists seemed to take it rather personally when their devices didn’t work as well in practice as in theory: They blamed IUD failure on the “angry uterus,” as though the tissues that responded to the insertion of the IUD—and sometimes perforation by it—with infection, pain and bleeding had done so as a reflection of the woman’s anger over the device’s control. Strangely, no one had bothered to do any studies of the measurements of the womb before 1964, when Hugh Davis and his collaborator Robert Israel used 20 silicone rubber casts of wombs obtained via hysterectomy to estimate a range of “normal” uterus sizes. Davis, after this promising beginning, went on to invent the infamous Dalkon Shield, a device linked to at least 15 deaths and thousands of cases of miscarriage, infection, sterilization and chronic pain.

The name chosen for the Dalkon Shield was no accident: It wasn’t long before groups interested in population control began to refer to the IUD as a “weapon” in the war against the enemy, “the fertile female body.” The weapon’s general effectiveness was deemed more important than its safety for the individuals using it. “The consensus at the 1962 conference on the IUD,” Takeshita notes, “was that it was impractical to screen out patients with potential health risks if this method was to be an effective tool for population control.” This policy treated women as a monolithic enemy rather than as individuals with unique sets of risk factors and differences that could lead to a wide spectrum of outcomes resulting from use of the IUD.

A perfect storm of limited birth control choices, questions about the safety of the birth control pill, the Food and Drug Administration’s limited regulatory oversight and the dismissive attitudes of healthcare providers toward women’s complaints led to the too-fast widespread use of IUDs in the United States. In chapter 3, Takeshita describes the change IUD researchers made in the 1960s, as middle-class women began using the devices in greater numbers, “from the view of users as uniformly underprivileged, undereducated, and excessively fertile women, or targets of population control.” She charts how the fallout from the Dalkon Shield tragedy in the 1970s, as well as from other devices that had similar problems, changed the trajectory of IUD development and safety. During this time, Takeshita writes, the monolithic woman conceptualized by population control advocates began to splinter into specific IUD user groups—teenagers “who ‘could not keep appointments to receive’” birth control pills; racial minorities targeted for “negative eugenics”; married middle-class mothers, for whom the devices were considered less risky; and users in the global North versus the global South. The IUD shifted from population control device to its paradoxical position as both controller and that which gives control: “The ‘fit-them-and-forget-them’ population control method has now become a ‘hassle-free contraceptive’ for appreciative consumers,” Takeshita notes.

The book suggests that not much has changed in U.S. biopolitics since the 1970s. Chapter 4 takes up the accusation by those opposed to abortion that the IUD is an abortifacient rather than a contraceptive. Takeshita notes that each side in the debate—those who advocate for women’s access to birth control and those who advocate for its elimination—uses both science and arguments for women’s autonomy to argue, respectively, for and against IUDs. Physicians who are morally opposed to IUDs, she notes, focused on the religious woman’s right to full disclosure about the way the devices work. Antiabortion activist John Willke, for example, argues that the IUD causes “micro-abortion.” Meanwhile, advocates for access to birth control successfully laid sufficient scientific groundwork to defend the argument that the IUD seemed most likely to prevent fertilization itself rather than implantation of a fertilized ovum. In this way, both sides work—whether they want to or not—toward a middle ground at which the individual woman can make her personal choice based on the abundance of information each side has made available.

In chapter 5, Takeshita moves to the present, noting that after she had her second child, she had her doctor insert a Mirena, an IUD that releases a synthetic hormone and prevents pregnancy for five years. She describes this act as one of “reproductive self-determination.” This personal anecdote echoes the larger change in perception of the IUD as a convenience for women living in the global North. Yet women in the global South—“less modern women”—haven’t had it as easy. Takeshita writes that these women are “implicitly written off as being not modern enough to appreciate the new technology” by developers of hormonal IUDs, in part because nonhormonal devices are already in use and cost much less. The gap is evident in the United States as well—Mirena costs much more than the older, copper-based IUD.

Like many books that derive from dissertations, as I assume this one is, the jargon is abundant, and the author frequently tells us what she’s going to tell us—and occasionally tells us again. In spite of its academic density, however, The Global Biopolitics of the IUD weaves a fascinating and understandable history of a device that has harnessed women and that women have harnessed to control fertility, in ways that vary across time, space, ethnicity and socioeconomic status, even as it shaped scientific and political discourse.

Emily Willingham is a biologist and science writer. The author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to College Biology, she earned a Ph.D. in biological sciences from The University of Texas at Austin and completed a postdoctoral fellowship in pediatric urology at the University of California, San Francisco. She blogs about science and society at The Biology Files (http://biologyfiles.fieldofscience.com/).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.