This Article From Issue

March-April 2008

Volume 96, Number 2

Page 160

DOI: 10.1511/2008.70.160

The Science of Leonardo: Inside the Mind of the Great Genius of the Renaissance. Fritjof Capra. xxii + 329 pp. Doubleday, 2007. $26.

In writing The Science of Leonardo, Fritjof Capra has made splendid use of a remarkable scholarly tool: The National Edition of Manuscripts and Drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, begun in 1964 by the Florentine publishing house Giunti and now at last complete. This massive project provides facsimiles of each surviving page on which Leonardo ever put a mark, along with two transcriptions of each of his written texts (most of which were composed in his famous mirror writing): one that retains his peculiar spelling and punctuation, and another that hews more closely to modern Italian (a language that has changed far less over the past five centuries than English has). Austrian-born and multilingual, Capra reads Leonardo's Tuscan vernacular comfortably enough to have consulted some of Leonardo's original manuscripts and the facsimiles, providing his own English translations of the texts. As a result, this widely curious physicist's encounter with Leonardo has an immediacy that makes his portrait of his subject unusually compelling.

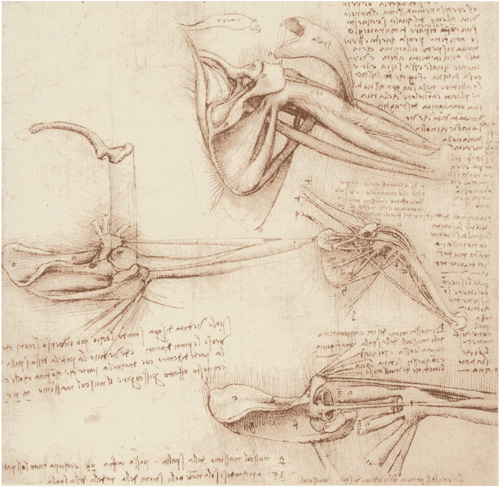

From The Science of Leonardo.

Leonardo, despite his phenomenal intelligence, good looks, athletic ability and charm, labored all his life against a terrible handicap: He was born illegitimate, the child of a notary, Ser Piero, and a peasant girl from the Tuscan hamlet of Vinci, Caterina, both of whom eventually married partners of their own social station. After spending his early childhood with his elderly grandparents, Leonardo eventually moved into his father's more elegant household in Florence. However loving this new environment may have been, the boy's status as a "natural" son singled him out for a second-class education. Leonardo attended an elementary "abacus school," where he learned reading, writing and arithmetic. Then, rather than sending the boy to learn Latin, an essential skill for any ambitious man in Renaissance Italy, Ser Piero instead apprenticed him, at age 15, to the artist Andrea del Verrocchio.

Verrocchio was a great sculptor, a good painter and a shrewd mentor. But this association with the manual arts would mean that Leonardo labored for the rest of his life under a cloud of social and intellectual inadequacy, dependent for his physical survival on the whims of lordly patrons and isolated from the very people who shared his fascination with the natural world.

Most of all, though, this training with Verrocchio ensured that Leonardo saw drawing as his most essential activity, and he drew with maniacal dedication. To Renaissance Tuscans (not only artists), drawing, disegno, was more than a matter of imitating nature; it was an intellectual and analytical activity of the highest order.

As Capra shows, Leonardo's drawings are not just a record of his observations. In a real sense, he used them as a kind of investigative tool. Drawing sharpened his eyes to the point where he could follow the eddies of surging water, or the flight of birds, with extraordinary precision, first breaking down individual motions and then synthesizing them in images that, as Capra demonstrates, are diagrams rather than snapshots of flowing water, wriggling babies, growing plants.

Unfortunately, aside from a set of more than 60 illustrations the artist drafted for his friend Luca Pacioli's essay On Divine Proportion, Leonardo never published any of these marvelous images. He put a few—for example, his huge cartoon for the Virgin, Child and St. Anne (now in the National Gallery, London)—on public display and kept the rest hidden away in his notebooks.

Capra, a prolific, successful writer, sees Leonardo's isolation, so different from the gregarious life of a university professor, with particular poignancy. He asks his readers on several occasions to imagine how differently the history of science might have developed had Leonardo's ideas and attitudes been more widely known in the 16th century.

The Science of Leonardo argues convincingly that this keen observer of nature was also a gentle soul in an age of shocking cruelty. He was, for example, a vegetarian, and he harbored no doubts that animals had souls; his drawings show cats, birds and horses with the same piercing, intelligent eyes and the same fierce dynamism as human beings. Unlike his contemporary Machiavelli, who wrote of conquering rivers, Leonardo declared that rivers could only be coaxed—and his terrifying drawings of rivers in flood, possibly inspired by a real cataclysm that struck Rome in 1514, show how profoundly he respected the power of nature. Leonardo described his famous painting of the Battle of Anghiari, created for the Florentine city hall, as an image of war's folly rather than its glory (even if the City Council may have seen it otherwise).

In an age obsessed with the ancient past, Leonardo's focus on nature's here-and-now seems anomalous. But in fact many of his drawings reflect the long, arduous program of self-instruction by which he tried to fill the gaps in his own education. The dazzling liveliness of Leonardo's images makes it hard to believe that they could derive from any source but life itself, and yet Capra discusses how two drawings, one of the male reproductive system and one a cross-section of the human head, clearly reflect ancient and medieval accounts of human physiology rather than Leonardo's own firsthand observations. Similarly, I suspect that some of his mechanical drawings may be based on ancient manuscripts: His armored car may have its source in a strange text called the Notitia Dignitatum, an illustrated ancient miscellany that lists the seven wonders of the world, types of Roman legionary standards, and war machines (some of the many surviving copies also discuss the noises that animals make).

In fact, the Renaissance obsession with ancient texts and ancient ruins produced two contradictory ways of thinking. One, which Capra describes concisely, was the inordinate respect granted to ancient authorities, such as Aristotle on cosmology, Galen on medicine or Pliny the Elder on natural history. Yet the careful collection and scrutiny of ancient manuscripts and ancient ruins also fostered a sharp empirical and critical spirit, which was needed to distill a reasonable version of Aristotle, Galen or Pliny from a vast series of manuscripts, every one different and every one imperfect in some way. Skepticism inevitably flourished alongside respect. Sharp eyes trained to see through crabbed handwriting and fragmentary buildings scanned the rest of the world no less attentively.

Even though he was a great and secretive genius, Leonardo managed to forge close friendships with a wide variety of people, from humble apprentices to the king of France. And he was not the only person to consign tantalizing thoughts to manuscripts that were never published. The genial scholar Angelo Colocci, whom Leonardo must have met in Rome, also filled thousands of pages of manuscript with notes on measurement. What's more, Leonardo's friend Donato Bramante, another "illiterate" in Latin, scrutinized ancient Roman architecture with the same analytical, empirical eye that Leonardo applied to nature. Bramante's work visibly changed the face of Renaissance Rome and its architecture.

Unlike some of Bramante's designs (such as the crossing of St. Peter's Basilica) that can be readily admired today, Leonardo's physical constructions—including a mechanical lion and sets designed for pageants—have not survived. But they may have exerted a more powerful influence on his contemporaries than we realize, as Leonardo himself may have, through conversations.

Appropriately, The Science of Leonardo itself has the feel of an open-ended conversation. The book is a delight, lucid and spirited, and it sparks a whole series of ideas and questions for further investigation (in my own case, about Leonardo's sense of history). Most movingly, Capra hopes that this great artist still retains his ability to inspire. He does, beyond question.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.