This Article From Issue

January-February 2004

Volume 92, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/2004.45.0

Einstein's Luck: The Truth Behind Some of the Greatest Scientific Discoveries. John Waller. xii + 308 pp. Oxford University Press, first published in the U.K. in 2002. $30.

Scientific discovery calls for a difficult balance: Intrepid advocacy of new ideas must often be tempered by the results of self-imposed trials. When should conflicting data be taken as disproof, and when should they be discarded as tainted? In the aftermath of any scientific advance, historical questions remain vexing: Who really discovered what, and how? Addressing these dilemmas should open our eyes to fuller truth. John Waller, a research fellow at the Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at University College London, has assembled a group of cases that give rise to such questions in Einstein's Luck. In this lively and engaging book, Waller interprets the work of other historians (with due acknowledgment) for a wider circle of readers.

The first part of the book contains cases in which Waller considers that a scientist was "right for the wrong reasons"—cases characterized by "the making of very bold claims on the basis of less than comprehensive evidence." In Waller's account, Louis Pasteur was not above suppressing data that did not support his arguments against the spontaneous generation of life. Likewise, he explores criticisms that Robert Millikan excluded observations that did not fit his preconceptions about the unique charge of the electron and that Arthur Eddington fudged his famous 1919 verification of Einstein's theory of general relativity by throwing out two-thirds of his data (which supported Newton). Waller discerns similar self-confirming selectivity in experimental studies of "scientific management" by F. W. Taylor and the "Hawthorne experiment" on productivity.

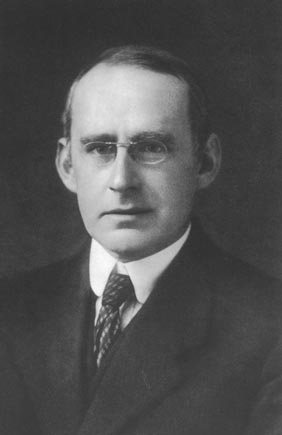

From Einstein’s Luck.

Waller concludes that, especially in its formative stages, science progresses through tentative hypotheses that require a nuanced reading of experiment and some exclusion of contradictory observations. Still, Waller faults Eddington for massaging his data. In the long run, Einstein was right, but Eddington's demonstration was flawed by his excessive zeal to vindicate the new theory. Waller judges that this brought Einstein's theory into the mainstream perhaps five years earlier than would otherwise have occurred, but at the cost of means that serve "to debase the whole scientific enterprise."

These cases highlight both the danger and the importance of such scientific risk-taking. By itself, Eddington's result was not sufficient. However, Waller does not dwell on the larger picture we have from many more-accurate measurements that came afterward confirming the correctness of Einstein's prediction. Can these absolve Eddington's sins? Here Waller does not consider the theoretical issues of the beauty and logical force of Einstein's theory, which moved Eddington and the others who early on opted for the theory even in advance of definitive experimental confirmation. Given that this process takes a long time, such arguments are of real importance. Waller's emphasis on experimental cruxes would have been enriched by including these larger questions.

The second part of the book concerns "sins against history"—cases in which the way a scientist "is generally understood and depicted in textbooks, television documentaries, and many biographies, is wrong on major points of fact and interpretation." How should we understand Charles Darwin's reliance on use-inheritance (the idea that the degree to which a parent uses an organ will determine whether its offspring inherit it in a highly developed or atrophied state), Thomas Huxley and Samuel Wilberforce's debate over evolution, James Young Simpson's defense of medical anesthetics? Here, Waller rightly emphasizes that we should consider earlier theories in the context of their own time, rather than only in relation to presently held views.

In other cases Waller discusses, one individual was given excessive credit for a discovery that really was the product of many: John Snow and the story of the Broad Street pump as the key to the spread of cholera, Gregor Mendel and the "laws of heredity," Joseph Lister and antisepsis, Charles Best and insulin, Alexander Fleming and penicillin. Here, Waller's brief treatments are cautionary tales about the human tendency to build simplified stories that gloss over the true richness and complexity surrounding an important discovery. Sometimes the crux is the protagonists' own appetite for credit and glory (as with Lister, Best and Fleming), but sometimes the protagonist never put forward the claims long afterward made on his behalf (as with Mendel). Waller concludes that we should be skeptical about stories that give one individual exclusive credit for a complex discovery.

Although Waller cautions that his examples "are not offered as representative of all science or all scientists," the general tone of his book privileges them, especially since he does not present counterexamples. Historical objectivity requires more than debunking, as salutary as it may be. After all, Einstein was not just lucky. How did Pasteur put it? "Chance favors the prepared mind."—Peter Pesic, St. John's College, Santa Fe, New Mexico

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.