Free Internet Access to Traditional Journals

By Thomas J. Walker

Can scientists find ways to share published research without high cost? The experiences of one society suggest it can be done cheaply, even profitably

Can scientists find ways to share published research without high cost? The experiences of one society suggest it can be done cheaply, even profitably

DOI: 10.1511/1998.37.463

The verb "to publish" has special meaning in the scientific community. Scientific, medical and engineering research is paid for by the public, private industry or donors; the results, essential to the advancement of knowledge and the investigators' careers, are reviewed by peers and shared with the larger scientific community primarily through their publication as articles in journals.

Once published (the copyrights having been signed over by the authors), journal articles become a commodity that can be sold by publishers to a nearly captive market: university libraries. In recent years this market has experienced, ironically, both a proliferation of product and a dramatic spiraling of prices—the prolonged "serials crisis" during which libraries have canceled subscriptions and forgone book purchases to pay for the most essential journals. In a world brimming with new knowledge and new ways to find it, there have appeared pockets of information poverty and local hardship.

Linda Huff

Set against this backdrop has been the rapid development of the Internet and the World Wide Web (the interface that allows data files, graphics, pages, text and even movies to be "served" to personal computers around the world). These technological leaps make it likely that access to scientific knowledge will be revolutionized by "on-line" publishing, the questions now being "when?" and "how?" In a few years, in my view, current issues of all journals will indeed be available on the Web, and so will complete backfiles of all major journals. But I am concerned about how open and economical this new form of publishing will be. Will this vast Internet library—with holdings exceeding those of all but a few of the world's libraries—be surrounded by toll gates charging substantial fees for access to this knowledge? Is there not a way to provide open access to scientific knowledge to all, to make the Internet effectively an international public library for peer-reviewed research results?

On the Web, publishers are now beginning to charge for access to journal articles on-line through subscriptions, site licenses and "pay-per-view" plans. These toll-gate approaches are an extension of the current economic structure of scientific publishing and are being developed largely (though not exclusively) by the organizations that benefit most from that economic structure. Many of those who do the research and write the articles do not share these economic interests, nor do many of the disciplinary societies to which they belong. Those who pay for and do the research generally do not want the published results to become a commodity resold at high cost. In my view, societies have important alternative options for their journals during the transition to our collective digital future—options that can serve the research community, provide institutions some relief from the serials crisis, finance on-line publishing and make knowledge available to all. In this article I shall describe the experiences of one small scientific society that has ventured into low-budget electronic publishing (without putting up toll gates). Based on these experiences, I shall show that societies can pay for delayed free Internet access to all articles in their journals by selling immediate free access to those authors who want it. In addition, some societies currently finance publishing through per-page charges that are paid by authors or their grants or institutions. Such charges now help hold down subscription prices; in the future, similar charges might finance free access.

In 1665, the Royal Society of London published the first issue of the first scientific journal. The journal's purpose was to disseminate the results of members' research, allowing scientists to reach a wider audience than they would by exchanging private letters. Journals soon became a means of establishing priority for new discoveries, were accepted as the permanent record of research and were archived by libraries. Peer review of all or most articles was instituted as a means of screening and improving what was published. Citations to earlier articles provided a way to weave previous research into the fabric of the new.

For nearly 300 years, the numbers of journals grew steadily, mostly as investigators founded new societies to promote new or newly important scientific disciplines. These societies helped members publish their research results by sponsoring one or more journals. Until the 1960s, most societies recovered publication costs largely from members' dues, which included a journal subscription. The number of articles published by each author was relatively small, and many members did not publish at all. Library subscriptions were not a major source of income for publishers. Although scientific societies published most science journals, some were published by other nonprofit institutions such as universities, museums and governments. Commercial publishers were generally not attracted to the field because there was little potential for profit.

The postwar science boom in the U.S. vastly increased the education and employment of scientists. The number of U.S. science and engineering Ph.D.'s awarded each year tripled between 1958 and 1968 and continued to increase until the early '70s. With many more scientists and with support of research easily available and generous, submissions to journals surged. The surge did not abate when grants and academic jobs eventually became more difficult to acquire. After all, an important indicator of research success is the number of papers published, and investigators seeking jobs, grants, tenure and promotion wanted to improve their chances in an increasingly competitive environment.

Societies soon faced the problem of having to reject good manuscripts and to delay publication of accepted manuscripts because their journals and their ability to subsidize members' publication were at capacity. Granting agencies faced the dilemma of paying for research that could not be published in a timely fashion or at all. In 1961, to alleviate the financial strains on journal publishing, the federal government approved the payment of page charges (fees for publication) by federal agencies and from federal grants to nonprofit publishers. Societies quickly took advantage of this new source of revenue to publish more pages in their established journals and to start new journals. For example, in my field, the Entomological Society of America approximately doubled the size of its Journal of Economic Entomology in the four years after it began page charges, and it started a new journal, Environmental Entomology, which by its second year exceeded the pre-page-charge size of JEE. Nonetheless, societies did not come close to satisfying the burgeoning need for publishing outlets.

Commercial publishers seized the opportunity to offer scientific investigators new outlets for their manuscripts. They started new journals in long-established fields; but, of greater impact, they identified new or newly popular research areas (Microbial Ecology, Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, Insect Biochemistry, to name a few familiar to me) and established journals in those specialties. In each case, the publisher would invite carefully chosen eminent scientists in the specialty to be members of an editorial board for the journal. Most such scientists were willing to be so recognized and to help establish a journal that would increase the status and publishing opportunities for their field. With the endorsement of an international board of distinguished scientists, the publisher attracted the subscriptions and the manuscripts needed to start the journal on its way to becoming indispensable to investigators and to the libraries that served those investigators. Adding to the attraction of these journals to authors was their lack of page charges.

The troubles for libraries were initially a simple outgrowth of the proliferation of new knowledge and the acceleration of scientific and technical advances. As fatter issues and more journals were published, research libraries found it increasingly difficult to pay for all the old and new journals that their clients needed. Between 1960 and 1970, 12 established research universities increased their acquisitions expenditures in constant dollars by 150 percent and the number of volumes by 117 percent. This growth could not be sustained. In the following decade their expenditures increased only 2 percent, and the number of volumes declined by 11 percent (Cummings et al. 1992).

Edward Roberts

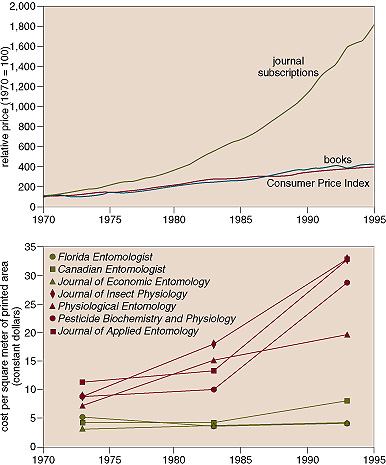

The 1970s witnessed the beginning of extraordinary increases in the real prices of science journals. Whereas the costs of scholarly publishing in general, as represented by prices of hardbound books, closely followed the Consumer Price Index, the average prices of science and technical journals diverged upward (Figure 2). The trend has continued. Since 1986, the 121 members of the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) have spent 124 percent more on serials to purchase 7 percent fewer titles.

By 1994 there was much interest in electronic publication of scientific research as an economical alternative to traditional paper publishing. Clearly the sheer volume of all those pages printed and shipped on paper was a major factor in the cost spiral, and digital technology presented many new, more flexible options for high-volume storage, searching and the retrieval of research results. In every discipline scientists were, by this time, equipped with sophisticated computers that were connected (in most parts of the world) to the Internet, and they were already using them routinely to exchange unpublished research information.

The Florida Entomological Society, to which I belong, began in 1994 to examine these trends and consider a move toward electronic publication. I conducted a crude study of the trends in journal pricing in our field. Although there are varying reasons for the steep increases in journal prices in many fields, I wondered whether the different economic models used by societies and commercial publishers were having differing impacts on pricing in entomology. For instance, commercially published journals seemed to be increasing subscription prices disproportionately. Did that simply reflect an increase in the amount of material published in these journals?

I selected three society-published journals (Florida Entomologist, Canadian Entomologist and Journal of Economic Entomology) and four commercially published journals (Journal of Insect Physiology, Physiological Entomology, Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology and Journal of Applied Entomology) and determined the cost to libraries of each square meter of printed matter in each journal in 1973, 1983 and 1993. Then I adjusted the results for changes in the Consumer Price Index. The three society journals, as it turned out, cost less initially, and their cost per square meter changed the least over the 21 years (–28 percent to +166 percent), in constant-dollar terms. The cost per square meter for the four commercially published journals increased an average of 271 percent. In 1993 a library's cost of access to a square meter of one of the three society-published journals was, on average, 14 percent of the comparable cost for a commercially published journal. The alternative means of financing available to societies—page charges and memberships—were helping keep costs down for libraries, but the cost of subscription-financed commercial publication was contributing heavily to the serials crisis even in our small field.

Every year libraries must cancel journal subscriptions to continue receiving other journals that are increasingly costly. (And publishers often raise subscription prices as their subscriber base shrinks, creating a feedback loop.) Unfortunately, rather than ending the libraries' serials crisis, the beginning of Web access to traditional journals may have intensified it. Publishers now offer licenses to electronic versions as add-ons to regular subscriptions. The Web versions enable library patrons to access and search the journals without leaving their office or laboratory computers, and many of them are enhanced with extra material and sophisticated indexing and search capabilities. But there is of course a cost for this service. For example, the American Chemical Society offers libraries site licenses for the Web versions of its journals for 25 percent more than for paper subscriptions alone. Ironically, then, in these early stages of the Web's evolution some libraries are paying more for journals because they are paying for two versions and for the enhanced access expected as technology allows it. Although indeed they are providing more service and convenience, this is not the world of "free" digital information envisioned by some prophets of the Internet.

Edward Roberts

Within some fields of science, meanwhile, alternative and economical do-it-ourselves models have emerged. Most notably, physicists and mathematicians now routinely submit their manuscripts as "e-prints" to an Internet server at the same time they submit them to traditional journals. If they rewrite a manuscript, they submit the new version, but the old one stays in the on-line archive, helping to resolve questions of priority in a more objective fashion than if only anonymous referees have access. The famous e-print server called "xxx" (its Internet address is xxx.lanl.gov) at Los Alamos National Laboratory currently handles 25,000 submissions annually at a cost of no more than $15 per paper, including overhead (Odlyzko 1998). Although most of the papers are eventually published, their e-prints are available more easily and are probably consulted more frequently. The founder of the e-print archive and its current overseer is physicist Paul Ginsparg, who started it by himself because it seemed a good use of the developing technology (Taubes 1993, Ginsparg 1996).

Investigators in many areas of physics and mathematics, where (in contrast to the life sciences) there is a tradition of widely circulating information in preprint form, thus have open electronic access to much of the recent literature in their fields prior to its traditional publication. But can free access be granted for the final, refereed articles in these and other fields? There are barriers to implementing such a model, but these barriers hardly mean there are not exciting prospects for new kinds of publishing, or for saving money doing it. Strangely, a small entomological society's electronic-publication project may demonstrate to larger scientific societies that they can grant such access and reap rewards from it—both in improved service to their members and financially. To understand this, you must first know the technology that makes free access affordable.

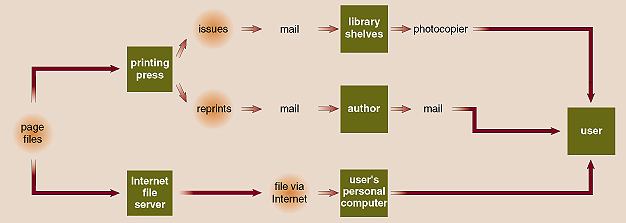

While serials prices were climbing steeply, printing technology was rapidly changing—moving from metal type-handling through the "paste-up" of type set on photographic compositors to the electronic page composition and platemaking of the present decade. It eventually proved very economical to transform the electronic files used to "image" printing plates into files that could be displayed and printed on remote personal computers.

Again, the mathematics, physics and computer-science communities have made special strides, developing and sharing software that produces files that can be printed equally well by a desktop, remote computer or traditional printing press (although these files are not easily used by those of us outside those communities). But in other fields, such as my own, the diversity of source files and the different nature of our work has required a format capable of working with various word-processor documents and graphic elements.

The Florida Entomological Society's success with low-cost electronic publishing is based on its use of the file format known as the PDF, or Portable Document Format (produced by Adobe Acrobat software). For about $1 a page, a journal printer can save individual articles as PDF files, which can be read and printed with free software that is available for computers using any major operating system. The articles retain the appearance of the printed originals; effectively, a PDF file is a stored photocopy-quality image that can be searched and read on a computer screen or used to make a faithful printout at home or in the office. The costs of serving journal articles this way are the cost of space on a a Web-serving computer and of preparing and maintaining table-of-contents files with hypertext links to articles. Web-server space costs an estimated 35 cents per megabyte per year, a PDF file for an average article is about 0.6 megabytes, and the average journal has 123 articles annually (Tenopir and King 1997). Thus posting a year's contents of an average journal should cost less than $26 annually. The user must of course have a Web connection, "client" software and, if hard copy is desired, a printer.

The Florida Entomological Society has about 450 members. In November 1994, a few weeks after free software to display and print Acrobat PDF files became available, the Society started posting all articles in Florida Entomologist (An International Journal for the Americas), its long-published (since 1917) refereed journal. Our start-up costs were less than $500. Since then, features have been added, but the total cost to the society of preparing articles for publication on the Web is less than $3 per page. From the beginning, the Florida Center for Library Automation (FCLA), which serves Florida's 10 public universities, has provided encouragement and permanent posting of all files on its Web server at no charge. Other research libraries should be expected to offer societies free posting for open-access PDF versions of their traditionally published journals. The service costs little to provide, and libraries are firmly on the side of convenient access for users. (This access is permanent, in contrast to site licenses for commercially published journals that must be renewed every year or so.)

Incorporated in the FES project more recently has been the posting of minimal HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) files in addition to the PDF files. Since the indexing robots of Web search services ignore PDF files, this was necessary to expose the full text of all on-line articles to the robots. Adding the HTML took about $300 to start and continues at a cost of $20 per issue. Next, the society installed on its home page a search engine that can find any article among its journal's on-line issues. This program searches the full text of the on-line HTML files, which link to the PDF files. For this service, the society paid $130 to the Internet company that prepared its home page.

Because the responses to the initial phases of its e-publication project were so positive, FES has recently initiated two new services. The first, begun in February, gives authors the opportunity to permanently post computer files that are pertinent to their on-line articles. These files, accessed via hyperlinks in the on-line tables of contents, can include color pictures, full data sets, and sound and video clips. The author pays a one-time fee of $45 for the service, and FES expects to earn an average of $40 per "AuthorLink."

Secondly, FES has begun to make back (pre-electronic) issues available at no cost on the Web. Inspired by JSTOR (for Journal Storage), a nonprofit organization that pioneered techniques for putting back runs of journals on the Web, FES has contracted to have all articles in the society's journal, from 1917 to 1994 (some 20,000 pages), scanned, read by optical-character-recognition software and indexed. After pilot tests were completed last year, the $12,000 needed for this contract (60 cents per page) was raised from industry and the University of Florida. The Florida Center for Library Automation is putting these files on-line as part of its digital library, where they will be accessible and searchable without cost to all Web users with the same software and to the same high degree as the electronic versions of the 650 Elsevier journals that FCLA has recently leased and can make available only to patrons of five participating libraries.

The Florida Entomological Society posts PDF files for all its articles at no extra cost to authors by taking the $3 per page cost of the service from its $45-per-page publishing charge. We describe this as furnishing our authors "electronic reprints," because, when printed, a PDF file is the equivalent of a paper reprint. But unlike paper reprints, electronic reprints are never used up and are available all the time nearly everywhere. Obviously, authors, if given the opportunity, should be willing to pay for electronic reprints.

Edward Roberts

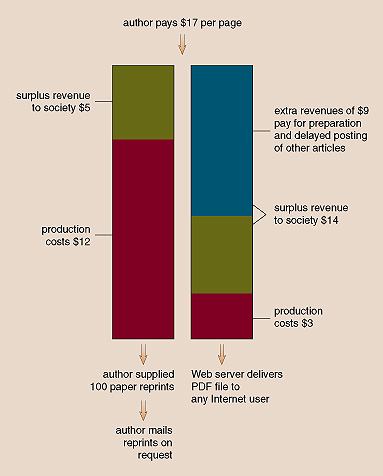

In fact the economics of electronic reprints are so favorable that societies should be able to finance free access to all their articles from the extra revenues generated by selling "e-reprints" to those authors who want their articles immediately posted in this way. Figure 4 illustrates how this would work. In the example shown, a society sells authors 100 traditional paper reprints for an average price of $17 per page, of which $12 pays for printing, packaging and mailing the reprints to those who order them. If this society were to sell electronic reprints—the option of having PDF files posted immediately so that anyone could download and print them—for $17 per page, it should cost no more than $3 per page to produce and post them, and the society would make $14 per page in reprint profits instead of $5. The extra profit ($9 per page) should more than pay for delayed posting of those articles for which authors fail to buy e-reprints. The details of this scheme will vary from society to society. For example, the average per-page price for 100 paper reprints varies at least from $15 to $43. Nonetheless, the difference in the costs of producing paper and electronic reprints will always be great, and that difference is what is used to open access to all articles after a delay of at least one year. (Without such a delay, authors would have no incentive to buy e-reprints.)

Edward Roberts

Societies depend on library subscriptions to help pay their publishing costs—not so heavily as commercial publishers, but enough to make them cautious about providing free Web access to their articles. The experience of FES, which has made all articles in its journal immediately and freely Web accessible since late 1994, is instructive. From 1994 through 1998, institutional subscriptions to Florida Entomologist declined 3 percent. In an attempt to separate the effects of the serials crisis from that of free Web access, I compiled data for four society-published, Web-inaccessible journals. These four showed an average decline in institutional subscriptions of 18 percent during the same period (Figure 6). Surprisingly, institutional subscriptions to Florida Entomologist for 1998 are up 5 percent from 1997. Should FES's experience not be repeated and library subscriptions falter, societies can recover lost income by raising the price of e-reprints, which would also reduce the percent of authors buying them and hence reduce the likelihood that libraries would cancel.

Are there concerns other than loss of library subscriptions that may make societies reluctant to provide their members and all others free Web access to their journals? I've thought of three. The first is loss of royalty income. Journals try to collect royalties for photocopies of articles that exceed those permitted under "fair use." Making articles Web accessible for free will reduce and eventually eliminate this income. However, royalty income is minuscule relative to total publishing revenues, and the extra profits from selling e-reprints should easily cover the losses. One national society grosses about 50 cents in royalties per published page, with a net of 30 cents (after the costs of copyright registration are deducted).

Edward Roberts

A more interesting concern is that making all articles accessible without cost in PDF format will detract from efforts to put traditional journals on the Web in attractive, interactive HTML format, such as is being done for a number of society-published journals. Those societies that already put enhanced HTML versions of their articles on the Web also post PDF files. By allowing authors to pay to have the PDF versions of their articles available for free, these societies will generate additional revenue for their e-publishing efforts. And additional revenue is needed, because enhanced HTML is costly. Exact figures are hard to obtain, but start-up costs are evidently $20,000 or greater, and maintenance costs are at least several thousand per month. The only specific figures I have seen are in a recent estimate for putting a society-published medical journal on line: $45,000 for one-time fees and $48,000 per year in recurring fees (for 2,600 pages annually, or $18.46 per page). Among the components of this estimate was $1.75 per page for the production of PDF files. If the society bought only the PDF files and turned them over to a library for permanent posting, annual costs would be $4,550 plus whatever had to be paid to make the links to the on-line tables of contents. Those societies not yet putting enhanced HTML versions on the Web might ask their members what sort of Web access they want and how it should be financed.

A final concern is that free access now will financially ruin societies in the all-electronic future, when issues and reprints are no longer printed and mailed. If societies acknowledge that their mission is to serve members, they should realize that restricting access to refereed research results, when free access has finally become affordable, is counter to that mission. They should avoid the appearance of trying unnecessarily to maintain the commodity status of journal articles and instead experiment with ways to reduce publishing costs by better use of digital technology in refereeing and editing. Societies can take comfort in the fact that they have ample time to prepare for change, because the end of central printing is not imminent. The printed page (which you now hold in your hand, enjoying its aesthetic quality, crisp readability and portability) has served the research community long and well, and it will not be abandoned until researchers, librarians, and publishers agree that there is a better way—and what that is.

Traditional journals will change rapidly once they go all-electronic. What the changes will be cannot be predicted, but their nature will be greatly influenced by whether access is free or by subscriptions, site licenses, and pay per view. Therefore it is important to compare these two economic models with a view of deciding which to pursue and which to eschew. The free-access model will revolutionize journal publishing whereas the current mix of subscriptions, site licenses and pay-per-view plans attempts to maintain current revenue streams, the greatest of which is from research libraries. (1) Publishers will no longer pay for printing and mailing issues and reprints, which now account for 30 percent or more of total publishing costs.(3) Libraries will no longer pay to display and preserve paper issues. Each library that subscribes to a journal and archives it binds the issues into book-sized volumes (at more than $6 per volume) and provides space for the ever-growing number of volumes at a cost of about $18 per volume (Getz 1997). Then, to maintain full-service access to the volumes, each library must pay an average of more than $3 per volume per year for staff and operating costs. Several hundred to several thousand libraries do this for each journal. Andrew Odlyzko (1998), an AT&T Labs mathematician who has done extensive research on journal publishing, estimates that the total cost to libraries for providing these services is $8,000 per article. For U.S. scholarly science journals the total savings would thus be approximately $5 billion (using the Tenopir and King data as above).

Edward Roberts

Let's first consider free access, which I advocate. If central printing is ended and access is free, this triad of large costs of the present system will vanish:

(1) Publishers will no longer pay for printing and mailing issues and reprints, which now account for 30 percent or more of total publishing costs.

(2) Libraries will no longer pay for subscriptions or site licenses to journals. The total probably exceeds $2.5 billion annually. Two recent articles estimated that revenues generated per article were about $4,000 (Tenopir and King 1997, Odlyzko 1998). If three-fourths of revenues are from libraries, the cost per article is about $3,000. In 1995, 6,771 U.S. scholarly science journals published an average of 123 articles (Tenopir and King 1997). Combining these estimates, the savings to libraries from subscriptions to U.S. scholarly journals alone would be $3,000 x 6,771 x 123 = $2.5 billion.

(3) Libraries will no longer pay to display and preserve paper issues. Each library that subscribes to a journal and archives it binds the issues into book-sized volumes (at more than $6 per volume) and provides space for the ever-growing number of volumes at a cost of about $18 per volume (Getz 1997). Then, to maintain full-service access to the volumes, each library must pay an average of more than $3 per volume per year for staff and operating costs. Several hundred to several thousand libraries do this for each journal. Andrew Odlyzko (1998), an AT&T Labs mathematician who has done extnsive research on journal publishing, estimates that the total cost to libraries for providing these services is $8,000 per article. For U.S. scholarly science journals the total savings would thus be approximately $5 billion (using the Tenopir and King data as above).

The chief costs that would continue in the free-access model are those of editing (including supervision of refereeing and revision) and composing. These costs are sizable, but Odlyzko gives data indicating that $300 to $1,000 per article should be sufficient. Another continuing cost would be server space and maintenance, estimated above for the PDF files of an average journal, at $26 per article per year for each posting site. (The megabytes per article will doubtless be greater and the costs correspondingly higher—except that the costs of digital technology continue to decline.) The chief new cost will be digital archiving, and that will not be trivial. Both the serving and the saving can and should be done by research libraries and at a small fraction of the cost of the traditional versions of the same two functions.

In order to provide free access, the publisher will have to be paid up front, but if investigators and their institutions believe free access is worth continuing, they can surely find ways to redirect funds to maintain it. For example, journal subscriptions currently cost University of Florida libraries about $900 for each article published by UF researchers. Thus redirected subscription savings alone could probably pay publications costs. The critical point to remember about free access in the all-electronic future is that the total cost will be much less, and it will be borne by the same parties as pay for the present system—namely investigators and their grants and institutions. The principal difference will be that most of the money going to publishers will no longer flow through the institutions' libraries.

The other economic model (subscriptions, site licenses, and pay per view) requires that libraries buy site licenses to give their patrons access to the publishers' digital files. It permits individuals who wish to subscribe to pay their fees and get their passwords, but individuals who neither subscribe nor have a library that buys a site license are expected to pay prior to viewing in an Internet equivalent of a vending machine. Maintaining a controlled-access system has its own costs; it is easy to imagine that a society might spend more money maintaining subscription lists and passwords and dunning subscribers and maintaining server security than it would spend to prepare and serve articles.

An important consideration regarding the site-license system is that publishers possess the journal archives. Libraries will no longer own archival copies but will be required to lease the right to access the publishers' archives. Each time the leases are renewed, the prices may be renegotiated.

Free access to traditional journals is affordable and achievable. It is the right thing to do for those who pay for the research and for those who do it. Scientific societies can provide it and profit from it. Societies that offer free access will gain modestly in revenues and in their competition with commercial publishers for the best manuscripts, and they will gain greatly in their service to their members and the public. Members should therefore make sure their societies provide it. By establishing a tradition of free access now, investigators can guarantee free access in the all-electronic future. Libraries should help by establishing partnerships with societies to provide permanent posting of freely accessible articles and to archive the digital versions in preparation for the time when digital versions are definitive. Taking action now can secure an information highway where toll gates do not limit access to the literature of science.

The author thanks Mary Case, James Corey, Stevan Harnad, Donald King, Rosalind Reid and Andrew Odlyzko for providing helpful comments and data during preparation of this article.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.