This Article From Issue

July-August 2002

Volume 90, Number 4

DOI: 10.1511/2002.27.0

Eye of the Albatross: Visions of Hope and Survival. Carl Safina. xx + 377 pp. Henry Holt and Company, 2002. $27.50.

Few birds differ more from people in their use of the planet than albatrosses, who spend nearly 100 percent of their existence on the sea or in the air above it. Their brief sojourns on land are solely for the purpose of raising their young, generally on small, remote islands. But in Eye of the Albatross, Carl Safina, with the help of a bird named Amelia, shows us how our world increasingly intersects with that of the albatross.

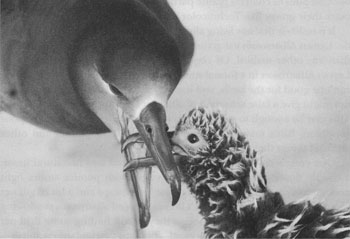

From Eye of the Albatross.

Thought-provoking, witty and beautifully written, the book recounts dramatic adventures (both human and avian), philosophically explores life and death, and chronicles the relationship between humans and nature. This is an honest first-person account of field biology in action. Safina, a top-flight conservation biologist specializing in seabirds, lucidly explains ecology and evolutionary biology and eloquently states the need for conservation. Founder and director of the Living Oceans Program of the National Audubon Society and a MacArthur fellow, he won a Lannan Literary Award for his first book, Song for the Blue Ocean, and will most likely receive additional awards for this one.

"An albatross," Safina tells us, "is a great symphony of flesh, perception, bone, and feathers, composed of long movements and set to ever-changing rhythms of light, wind, water." Albatrosses have incredibly long and narrow wings—the longest of any bird. These wings are held absolutely still in flight by locks at the shoulder and elbow, turning the bird into a biotic glider kept aloft by the turbulence of air off the surface of the ocean. "The greatest long-distance wanderer in the world," the albatross flies almost perpetually, using an entire ocean as its front yard and annually covering distances equivalent to circumnavigating the earth at the equator three times.

From Eye of the Albatross.

These birds have a natural life span measured in decades. They take several years to reach sexual maturity, and many breed only every other year. Both parents take turns incubating a single egg for two months and then alternately brood the chick and return to the sea for food for another six months or longer.

Safina meets Amelia, a Laysan albatross, when he joins a collection of ornithologists and other field biologists on Tern Island in the Northwest (Leeward) Hawaiian Islands, where Laysan and black-footed albatrosses join other seabirds to nest. Researchers scoop the massive Amelia off her nest a meter or so from their barracks and tape onto her back a satellite transmitter, which will allow them to follow her amazing travels in search of food.

Safina provides a plausible narrative of Amelia's journey, describing her behavior and how she presumably perceives her world as she navigates: "What to us is trackless ocean is to her recognizable territory, a familiar mosaic riddled with scents and signs." Amelia's departures from Tern Island—be they for an 800-kilometer "short" flight or a two-week round-trip of 6,500 kilometers to rich subarctic currents—are also points of departure for Safina in his exploration of the albatross's world.

Safina travels literally along the Hawaiian chain to Laysan Island and Midway Island (more than 90 percent of Laysan albatrosses nest on these two islands), East Island and oceanic points along the way. He encounters hundreds of thousands of nesting seabirds of many species and much smaller numbers of seals and sea turtles, and he joins the biologists studying them in wrestling down endangered monk seals (to test for morbillivirus), sampling tumors on endangered green turtles and tagging tiger sharks to determine their home range and local population size.

He also travels figuratively, going back in time to describe the wanton slaughter of albatrosses and other once-abundant seabirds for feathers, food or "sport." He shows us that Samuel Taylor Coleridge's image from "Rime of the Ancient Mariner" (Safina quotes from the poem liberally) needs to be updated: We humans are the burdens albatrosses carry around their necks—not vice versa. Mostly in the latter half of the 19th century and the early 20th century, the Japanese and others plundered the nesting colonies, slaughtering well over 5 million adults of a single species (more than the total number of albatrosses of all species alive today) and taking their eggs. According to Safina, an increase in adult mortality of just 3 percent can cause albatross populations to decline by 50 percent in 20 years. Despite some recovery during the 20th century, the World Conservation Union lists 83 percent of albatross species as "threatened."

The main threats today are in the water. Each year, perhaps 100,000 albatrosses as well as many other seabirds drown on the hooks of longline fishing vessels. Mincing no words, Safina describes what an albatross experiences as it is pulled to its death on a sinking hook. Overfishing of prey species may have an even greater impact on the populations of many piscivores.

When Amelia finds profitable foraging in the rich subarctic waters of the north Pacific Ocean, more than 1,500 kilometers from her tropical nesting grounds, Safina joins a fishing crew for a firsthand look at some of her competitors working the rich fisheries of Albatross Bank in the Gulf of Alaska. He finds a fishery that has begun to be managed in a sustainable fashion, and a "poster fisherman," who has found a way to fish with longlines containing thousands of hooks and yet avoid killing seabirds. Safina's chilling firsthand look at life on a fishing trawler is instructive about the promises and realities of conservation in commercial fishing.

Plastics, polychlorinated biphenyls and other toxicants are also hazards, killing wildlife even in the remote Northwest Hawaiian Islands. A poignant, shocking passage describes an albatross returned from the sea to feed her chick. After regurgitating some squid and fish eggs, she partially retches up a green plastic toothbrush, which she reswallows and then repeatedly attempts to "puke up," always without success—finally wandering away from the chick with the toothbrush still stuck inside her. Safina is profoundly affected:

In the world that shaped albatrosses, the ocean could be trusted to provide only food, parents to provide only nourishment. Through the care bond between parent and offspring passes the continuity of life itself. That the flow of this intimate exchange now includes our chemicals and our trash indicates a world wounded and out of round, its most fundamental relationships disfigured.

The main message from the albatross is this: every watery point on the compass is now conscripted into our all-consuming culture. . . . No place, no creature remains apart from you or me.

Somewhat surprisingly, Safina expresses hope, noting that the overt exploitation of albatrosses on land has been largely eliminated. Former slaughtering grounds are now sanctuaries. Thanks to efforts of conservationists, international agreements and action plans on longline fishing (the main killer of adults) have been crafted, and with the compliance of fishers, it can be made relatively safe for albatrosses; in some places, albatross populations began to rise after longlining pressure ceased. However, much remains to be done (see www.albatrossaction.org).

Writing with elegance and clarity, Safina lays the choices squarely before us. The bell tolls not just for albatrosses, but for us.—David Blockstein, National Council for Science and the Environment, Washington, D.C.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.