STEM Reads 2016

By Katie L. Burke, Fenella Saunders, Dianne Timblin

We’ve combed through our 2016 reviews to put together this selection of books we think readerly science enthusiasts would love to find in their stockings.

December 23, 2016

Science Culture Communications Scientists Nightstand

We’ve combed through our 2016 reviews to offer up a selection of books we think readerly science enthusiasts would love to find in their stockings. These books also represent a promising investment of gift-card dollars. After all, the better the book, the more it rewards the reader—often for years to come.

In addition, a holiday bonus: We couldn’t resist adding a few more titles from our personal reading lists over the past year. Some books are just too good not to share.

For more reading and gift ideas, check out our complete list of 2016 gift guides—there you’ll find something for science fans of all ages. If you’d like more recommendations, we have lists for 2015 and 2014 too.

Einstein. Written by Corinne Maier; illustrated by Anne Simon. NoBrow, 2016. $19.95.

Writer Corinne Maier and illustrator Anne Simon have previously paired on comics biographies of Freud and Marx. (Both books are well worth checking out.) Their third outing—a biography of Einstein, also in comics form—may be their most ambitious and successful yet. Maier and Simon don’t shy away from the complexities of the physicist’s persona, work, and times. The result is a book that portrays Einstein as a genius, yes, but also as a flesh-and-blood human, and his life is depicted in all its vitality and nuance. Simon’s colorful, rumpled figures perfectly embody the action Maier sets up and the vibrant dialogue she creates for them. Einstein explores the deep and manifold ways one life can alter science, as well as the ways science can alter one life. —Dianne Timblin

The Jazz of Physics: The Secret Link between Music and the Structure of the Universe. Stephon Alexander. Basic, 2016. $27.50.

For scientists who want new ways to think about physics, for musicians who want new ways to think about improvisation and the structure of sound, and especially for those who are both scientists and musicians and who find the interplay of these areas crucial to their work, The Jazz of Physics is an inspiration. Stephon Alexander is a physicist and jazz musician who has studied physics with the likes of Robert Brandenberger, Chris Isham, and Leon Cooper and studied music with the likes of Ornette Coleman and Brian Eno. Despite his impressive background, Alexander’s voice in the book is approachable: He explains physics and music concepts without the least bit of condescension, and he openly discusses moments in his own career when he felt insecure, intimidated, or struggled to understand something.

It’s clear that Alexander intends The Jazz of Physics to build on the writings of Stephen Hawking and Richard Feynman, whose works kindled his own interest in physics when he was in high school. He walks through complex physics concepts without leaving the uninitiated behind, starting out with the basics to keep readers on board. Then he moves on to explain headier concepts, such as the math of Fourier transforms and the differential equations that describe strings’ vibrations. Alexander folds in his experiences with hip-hop, various kinds of jazz, ambient music, classical music, and other traditions to discuss how they inspired and helped him maintain his enthusiasm for math, physics, and the patterns of the universe. He also walks the reader through the history of physics, beginning with Pythagoras’s search for the physics of harmony and describing the major breakthroughs that led to today’s ideas about cosmology, quantum physics, and string theory. The importance of music to the percolation of Alexander’s own scientific ideas is a major theme of the book—as is the vital nature of sympathetic mentors. (Alexander’s mentors advised him to pursue his music alongside his science rather than approach the field in the same way as other graduate students in his program.) Throughout, music becomes a source of accessible analogies to explain abstract concepts in quantum physics and cosmology. Exploring intriguing interdisciplinary questions—such as “Is the universe behaving like an instrument?”—Alexander invites readers to join him on his lifelong quest. —Katie L. Burke

I Taste Red: The Science of Tasting Wine. Jamie Goode. University of California Press, 2016. $29.95.

Wine columnist and former scientific editor Jamie Goode isn’t afraid to shake up the complacency of his colleagues with a little science. He discusses with one of them the mystery of younger and older Rieslings, which, despite containing the same percentage of sugar, appear to have different sweetness profiles. The discrepancy, he explains to his companion, might be explained by research on how the brain processes sensory information and combines it to create an overall perception: The fruity smell of the younger Riesling might fool our brains into believing its taste is sweeter. His colleague, affronted, responds, “You are having us all as fools.” Goode evidently kept his thoughts to himself at this point in the conversation, but he asserts in I Taste Red, “In truth, when it comes to our perceptions, we often are fools. Our brains are tricking us, but we trust what we perceive to be reality.” He goes on to explain that we “commonly experience the world in ways that combine the evidence of our different senses. It follows that the senses are not as separate as we have been led to believe.”

Goode digs into the flavor chemistry of wine, as well as individual differences in how we perceive flavors. These differences partly come down to genetics. For example, supertasters have a much higher than average number of taste buds. Of this group, psychophysicist Linda Bartoshuk says, “Supertasters live in a neon taste world,” explaining to Goode that they experience flavors three times more intensely than the nontasters, who make up perhaps half of the population. (The flavor perceptions of medium tasters fall somewhere in between these two groups: Medium tasters can discern more flavors than nontasters, but their tasting experience lacks the intensity of supertasters.) Goode even discusses the cranial physiology involved in how the olfactory and taste sensations blend. In the closing chapter, he proffers an intriguing suggestion. Rather than thinking of ourselves as having five or six senses, we should instead regard “all sensation—and all perception—as just one sense.” After all, he notes, it's only after our brains take in a mix of sensory information that we can separate individual components, and it takes special effort to do so. Finally, Goode turns to philosophy to shape and deepen the meaning of the research he's been discussing throughout. Regardless of whether a reader’s primary interest is science or wine—and certainly for enthusiasts of both—there’s much in this book to savor. —Dianne Timblin

Lab Girl. Hope Jehren. Knopf, 2016. $26.95.

At the end of the year, one of my jobs as book review editor and all-purpose book wrangler for American Scientist and Sigma Xi (the science research and honor society that publishes AmSci) is to make a decision that can be a bit painful for someone who loves books. From the truckload of books we receive in any given year, I select a small handful that we’ll keep on hand for future reference and possible follow-up coverage. (The reward is well worth a little pain, though. We donate all but these few carefully selected volumes, and I love imagining an actual truckload of books in the hands of so many readers.) Unquestionably, Lab Girl will be among the books we hang on to from 2016. Hope Jehren’s memoir gives readers a high-definition view of what it’s like to be a scientist—the day-to-day grind, the relationships forged through decades of collaboration, the ever-awkward work/life intersections (calling it balance here would diminish the difficulty), and the cherished, all-too-fleeting moments of inspiration and discovery. This book is a must-read. You’ll find Carolyn Beans’s full review of it here. —Dianne Timblin

Nathaniel Bowditch and the Power of Numbers: How a Nineteenth-Century Man of Business, Science, and the Sea Changed American Life. Tamara Plakins Thornton. University of North Carolina Press, 2016. $35.

Sharp-eyed readers may have noticed that a drone recently captured (and returned) by China had been launched by crew aboard the USNS Bowditch. The ship has been in service since 1996, and it’s the third U.S. naval vessel to be named after Nathanial Bowditch, a colonial-era mathematical phenomenon who, among other accomplishments, vastly improved navigation for mariners around the globe. Never heard of the man? You’re not alone. Yet his influence is still felt in disparate areas of contemporary life. For example, you can thank him for creating the aspect of organizational culture that reveres the standardized form—whether you know his name or not, you’ve probably felt Bowditch's influence while in the lobby of your doctor’s office, in the waiting area of the DMV, and at the bank counter. Thornton’s terrific biography brings Bowditch some well-deserved attention, and her prose is a pleasure to read. Check out Daniel S. Silver’s review here. —Dianne Timblin

Rust: The Longest War. Jonathan Waldman. Simon and Schuster, 2015. $26.95.

Abandoned in Place: Preserving America’s Space History. Roland Miller. University of New Mexico Press, 2016. $45.

Along with death and taxes, rust is on a short list of the inexorable. Given metal’s ubiquity in the modern world—as well as corrosion’s tenacity, afflicting nearly every metal—rust presents a problem. A big problem. As science journalist Jonathan Waldman reminds us, it threatens the stability of bridges, guardrails, nuclear power plants, and nuclear warheads. It undermines the safety of autos, planes, boats, and the water supply. It can shut down critical equipment of all kinds, from oil pipelines to server rooms. Even in space, rust blooms: Metals propelled beyond Earth’s atmosphere still corrode, thanks to atomic (instead of molecular) oxygen. Between prevention and mitigation, the U.S. government spends more on rust than on all other natural disasters put together. Yet the extent of the problem isn’t widely appreciated. As Waldman puts it, “rust ranks dead last in drama. There’s no rust channel.” Happily, he's here to animate the subject by showing how the work of corrosion engineers and inventors improves contemporary life, making it easier, more productive, and far safer than it otherwise could be. And the cast of characters Waldman introduces along the way is by itself worth the price of admission. (Read our full review here.)

Whether viewed alongside Rust as a kind of visual complement or enjoyed solo as an excellent volume in its own right, I highly recommend Abandoned in Place, a beautifully produced large-format book of photos and essays. Since the early 1990s Roland Miller has been photographing decommissioned equipment and facilities once crucial to the U.S. space program. His eye for architectural, clean-lined composition reveals his subjects in their full grandeur as astonishing artifacts of engineering that have come to endure the depredations of time and ruin. Certain close-up shots of structures awash with rust resemble the work of photographer Alyssha Eve Csük, whose intrepid excursions to photograph an abandoned steel mill occupy a chapter of Waldman’s book. Other times, Miller steps back from his subject, depicting massive structures as part of a broader landscape grown wild. His photo of a V2 launch site in White Sands, New Mexico, for example, shows a Hermes rocket still standing in place. Thick tufts of grasses have pushed up all around the spot where captured German V2 rockets had once been tested, but the distance allows everything to look intact enough to appear potentially functional—as if the testers had headed off to lunch just before the area entered a time warp. Waldman’s images of space-age ghost towns are strangely magnificent as well as magnificently strange. —Dianne Timblin

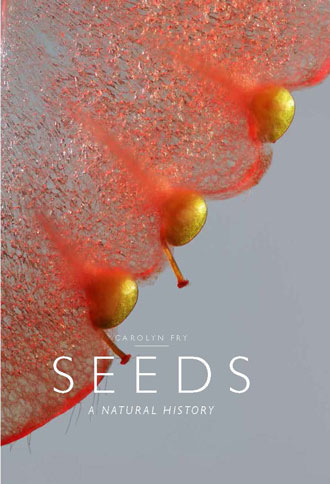

Seeds: A Natural History. Carolyn Fry. 192 pp. University of Chicago Press, 2016. $35.

Plant lovers will find much to enjoy in the pages of Seeds. Reviewer Peter H. Raven notes that author Carolyn Fry “has included superb and original images throughout the book, many of them illustrating, with light and scanning electron microscopy, aspects of plants and their biology that have rarely been presented as well. These images are not only a pleasure to view but also prove vital in conveying the book’s many compelling ideas and stories.” An attractive and informative volume, it discusses a dizzying array of plants and their reproductive strategies. Yet for all of the book’s breadth, Fry’s prose remains incisive and refreshingly clear. Read Raven’s review here. —Dianne Timblin

Slap Shot Science: A Curious Fan’s Guide to Hockey. Alain Haché. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015. $28.95.

All for the sake of science, author Alain Haché—a physicist and self-described “beer league” goalie—donned his hockey pads and faced off against some elite players from the National Hockey League. Haché “anxiously but happily” took slap shots at 85 miles per hour so he could apply some personal experience to his discussions of save percentages and the physics of goalie reflexes. Haché’s book, Slap Shot Science, is a follow-up to his earlier title, The Physics of Hockey. It covers some of the basics from the first book (but is lighter on the mathematics) and goes on to examine advances both in equipment and to the game's rules. He looks at the physics of the rink itself, as well as the science of ice, the mechanics of skating, and the effect of stick shapes on shots. He also focuses heavily on understanding and predicting hockey outcomes using statistics. If you’re an avid fan looking for a more scientific understanding of the game, or if you simply want to explore the physics puzzles of amazing saves, Slap Shot Science is a good read. —Fenella Saunders

The Tetris Effect: The Game that Hypnotized the World. Dan Ackerman. Public Affairs, 2016. $25.99.

Tetris: The Games People Play. Box Brown. First Second Press, 2016. $19.99.

Before encountering these books, I wouldn’t have guessed that the history of an iconic video game could read like a Cold War–era corporate thriller. But that’s exactly what Dan Ackerman and Box Brown deliver in these titles. Reviewer Jesse Shell explains that these books tell “a dramatic story involving multiple competing software companies, each grappling for control of a piece of software so simple that it can be coded with just 1 kilobyte of javascript, but that seizes and holds the human mind in a way that had never been seen before. Who would win the battle for Tetris was a matter of not only persuasive personalities, but who could best deal with the reality that inventions such as the Nintendo Entertainment System and the Game Boy were redefining what the term computing device even meant.” Ackerman’s The Tetris Effect is a vividly narrated, journalistic account, whereas Brown’s Tetris depicts the story in a comics format, an approach that perfectly aligns with his perspective of viewing games such as Tetris as works of art. Schell recommends reading both books, starting with Brown’s. As he observes in his review, “Just as two stereoscopic images help us see a three-dimensional picture, together these two books provide a depth of insight impossible to gain from just one point of view.” Read Schell’s review of both titles here. —Dianne Timblin

The Xenotext: Book 1. Christian Bök. Carriage House, 2015.

Bestselling poet Christian Bök has been working on his groundbreaking Xenotext project for well over a decade, and his work continues apace. To create what may be considered the first “living poetry,” he has collaborated with molecular biologists and bioengineers and has taken it upon himself to learn the science behind genetic engineering from the ground up. The Xenotext: Book 1 carves out the project’s poetic and philosophic terrain. Reviewer Michael Leong describes Book 1 as “a volume displaying staggering talent and genuine interdisciplinary imagination. It is at once rigorously scientific and rigorously literary. As Bök dynamically reflects on ‘biogenesis and extinction,’ poetic knowledge and scientific awareness intertwine as if in a double helix.” The book also attunes readers to signals of poems to come in Book 2, which will reflect the project's next phase. Meanwhile, Book 1 gives readers a taut matrix of poems to contemplate and enjoy. Read Michael Leong’s full review essay here. (To learn more about what the Xenotext project entails, check out our explainer.) —Dianne Timblin

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.