The Power of the Little Guy

By Fenella Saunders

Inventor Dean Kamen is resolved to engineer clean water for the entire world, and he might just do it.

July 14, 2015

Science Culture Environment Technology

Inventor Dean Kamen identifies with the small and the powerless. But he thinks technology can help level the field—and his resolution to engineer clean water globally for anyone who needs it could be a crucial step.

“As a little kid I was always the smallest kid in my grade, and I heard the story of David and Goliath,” Kamen says. “To me the moral of that story was ‘technology is cool.’ People say to me today, ‘well, how did you get that moral out?’ And I say well, these was this really little guy, David, and he had this really big problem, Goliath, but he had this little thing called a slingshot, and that little piece of technology took out that really big problem.”

Clip courtesy of SlingShot movie.

It could be argued that Kamen is no longer the little guy—he’s a remarkably successful inventor and entrepreneur. But his experiences continue to shape his work: “I think somebody that’s a really big person is somebody that doesn’t mind helping everybody else around them. A really big person helps everybody else be big, and doesn’t use their bigness to keep everybody else small.”

Kamen is the subject of a new documentary called SlingShot, named after his latest invention, which takes its moniker from that “little piece of technology.”

Best known for the Segway electric scooters, Kamen has been a prolific inventor, if not a household name—a point the film tackles first thing. It also gets out of the way many of the urban legends surrounding the Segway, particularly that the inventor drove it off a cliff (that was actually the owner of the company commercializing the devices).

Although the film has made the festival circuit, Friday, July 10, was its theatrical release. (A schedule is available on the movie’s website: http://www.slingshotdoc.com/)

Image courtesy of The Coca-Cola Company.

The film opens with the SlingShot device, a water purification system that Kamen hopes to get into rural villages in remote parts of the world. Then it cuts back and forth between the saga of bringing this vision to life and the rest of Kamen’s biography, moving from his childhood to his family to his other endeavors.

Beyond the Segway, Kamen is known for designing highly mobile wheelchairs, founding a robotics competition for kids called FIRST, and inventing home dialysis machines. The latter actually led to the SlingShot project, because dialysis requires pure medical-grade water, and Kamen was trying to figure out how patients could make that at home instead of companies having to ship it all over the country at high cost.

"Throughout my life I only start a project typically if enough credible people tell me ‘You’re nuts.’ Because then you know this must be a big problem," Kamen says in the film.

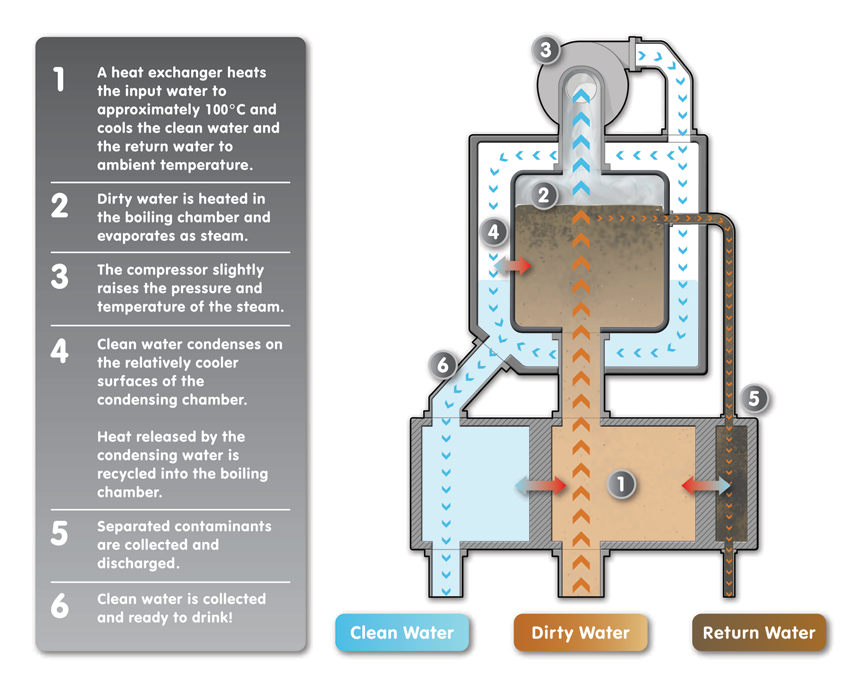

The technology behind the water purification is explained only briefly through a short animation, but that’s partially because the idea itself is relatively simple and quite well established. As Kamen notes, the trick comes in making the technology energy efficient, small, reliable, and easy to use—the definition of an engineering problem. In one tongue-in-cheek segment, Kamen seems to also be hiding behind the trope of not revealing his invention’s secrets as he jokes that various parts of the machine are made of expensium, unobtanium, unreliabilium, and Icantmaketwoathem.

Image courtesy of The Coca-Cola Company.

Kamen says that his device, called a vapor-compression distiller, recycles energy so that instead of taking 25 kilowatts (enough to power 20 houses), it uses about the equivalent of a hair dryer. It’s approximately the size of a director’s chair. You can stick the hose in any water source—a puddle, ocean water, even urine—and get pure water out. (In a 2008 segment on the TV show The Colbert Report, host Stephen Colbert dumps a bag of chips into the water to test it.) It is designed to produce 1,000 liters a day (enough for 100 people) for three years with minimal maintenance.

The documentary largely glosses over the ancillary problem of water purification with a distiller, which is that it uses electricity. Although Kamen mentions the issue of power generation briefly in the film, there’s no follow-up, leaving the question open. Evidently as he was developing the SlingShot device Kamen simultaneously worked on a flex-fuel generator to go with it, which was tested in 2005 in Bangladesh. The film makes no mention of this work, so viewers attentive to Kamen’s mention of electricity are left wondering if he simply expected that problem to be tackled by others.

Kamen is quick to share some startling facts about water usage. A 40 percent shortfall of water is expected by 2030. One in five Afghan children under five years old dies from consuming polluted water. In water-impoverished areas globally, the average time per day spent looking for safe water is four hours. “Every year we wait, a couple of million people die, most of them kids,” he says. Kamen purports that the availability of clean water will increasingly become a Western problem as well, citing pharmaceutical contamination of municipal water.

“The world is a race between all sorts of catastrophes and technical expertise,” Kamen states in the film. “We can’t let catastrophe win. So time is critical.”

Such personality-driven documentaries are prone to aggrandizement, and SlingShot is no exception: All of Kamen’s projects are important. He works nonstop. He personally, successfully fought off anti-Semitism as a kid. Nonetheless, the filmmakers humanize Kamen by showing his quirkier nature. For instance, there’s a slightly hokey running gag where he claps his hands together in place of the snap of the movie clapperboard. Among other quirks, he wears only denim and his silent partner is a giant teddy bear with a denim tie. He’s portrayed as a loner, without spouse or kids (even though his parents and brother are an important part of his life). He builds clocks and steam engines as a hobby. He is shown as artless on some of the distribution or business aspects of his work, although I wondered if this may have been a bit contrived—after all, his business has survived for 25 years.

Image courtesy of Moon Avenue LLC.

Kamen’s passion for education also shines brightly in the movie. He describes his annoyance that kids idolize athletes but don’t know a single famous scientist or engineer. As he says, it’s amazing that they think it’s awesome that a guy can get a ball in a hoop at a slightly higher percentage than someone else, but they don’t think about how we got the technology around us; it’s all taken for granted. So, 21 years ago Kamen set out to package science and math in a sports event, creating the FIRST Robotics competition. (I’ve had the opportunity before to speak with Kamen about his purpose in creating FIRST, and his enthusiasm is definitely infectious.)

However, it is troubling that Kamen’s own lack of children is brought up in contrast to all that he does for kids. Kamen is made to justify why he felt he needed to devote his life to his work, and is actually mildly chided on film by his mother for not becoming a father. This kind of public shaming of people who choose not to have children struck me as backwards and uncalled for.

Image courtesy of Moon Avenue LLC.

Kamen is made to face his demons squarely as well in the film, which he does with an admirable straightforwardness. The Segway was not the commercial success he’d hoped (although he’s still a great believer that in the future, crowding and pollution will make cars impractical for everyday movement). His FIRST Robotics competition hasn’t spread as fast as he wanted. He addresses the controversy his commercial partner, Coca-Cola, got into over water use in India in 2004, which caused nationwide protests in that country.

An interesting discussion in the film is that the technology itself isn’t necessarily the sticking point in getting clean water to the world, and Kamen explains well the learning curve in finding that out for himself. He describes how people in a 2006 trial in Honduras wouldn’t understand that taking the pure water and putting it in dirty containers would recontaminate it. The distribution to all the tiny towns, the education issues, those are the pieces that Kamen seems to struggle with the most. We are shown the many avenues he tries before he successfully partners with Coca-Cola. Apparently the company has pledged to be water-neutral by 2020, and Kamen’s machine meshes with that effort.

On the flip side, Kamen expresses lofty ideals about the future of his water machines, claiming they could act as agents of peace all over the world, by raising the profile of the United States among people as a country that helps out the little guy.

Kamen’s company built 15 machines that were successfully tested in 2011 in five schools in Ghana. His company then built 50 smaller, lighter machines for 2013 tests in Mexico, South Africa, and Paraguay. His goal is to get the cost of the machines down to a few thousand dollars apiece.

“You start putting all the pieces together and the chain will finally go from ‘it’s a crazy idea’ to ‘of course, it’s obvious,’” he says.

At the end of the movie, one is left with the impression of a man of incredible drive, deserving of great credit for some remarkable inventions and successes, yet who still keenly feels his setbacks and failures. One gets no inkling that Kamen intends to ever give up, and we’re left rooting for him to keep going, keep trying, keep inventing.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.