What Might Happen to COVID-19 Over Time?

By Katie L. Burke

The novel coronavirus is unlikely to go away completely after its first outbreak. People are only beginning to grapple with what comes next.

The novel coronavirus is unlikely to go away completely after its first outbreak. People are only beginning to grapple with what comes next.

To deal with the global pandemic of a novel coronavirus, people all over the world have scrambled to enact social distancing so as to reduce the speed with which the virus is spreading—key to reducing the strain on health care systems. But even as different countries have met that threat with varying degrees of success, they need to prepare for the aftermath. There is a real possibility that this outbreak is not the last COVID-19 curve we’ll need to flatten.

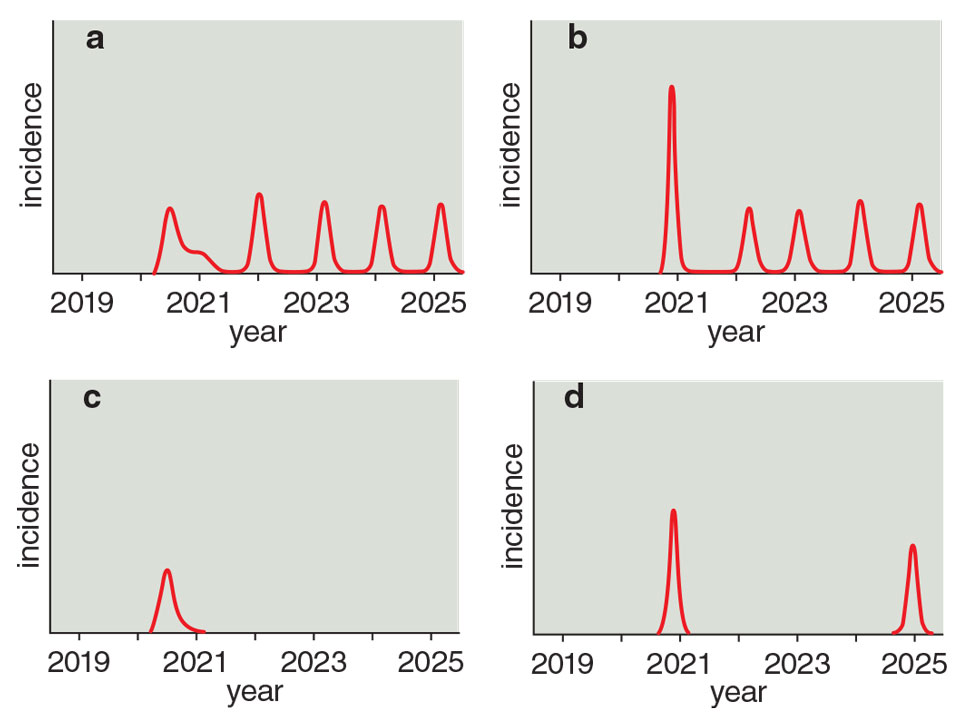

Epidemiologist Stephen Kissler of Harvard University and his coauthors published a paper in Science on April 14 that explores potential scenarios. “There’s a good chance that we’ll see some further waves of infection following this first one,” he says. Two crucial variables will affect the timing and number of resurgences: how well the virus is transmitted during warmer months, and how long immunity lasts in people who have recovered from the viral infection.

Adapted from Kissler, S. M., et al. 2020.

“It’s unlikely that the outbreak will just die out over the summer, as some have suggested,” Kissler says. His team’s study indicates that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing coronavirus disease 2019, or COVID-19) can spread at any time of year because there are so many susceptible people. However, if the virus becomes less transmissible over the summer months—which has been the case for some other coronaviruses and the flu—that could help reduce the rate of infection. For ongoing or emerging outbreaks, delaying the spread as the weather warms will be a boon.

How long immunity lasts will strongly affect when we might see a resurgence in infections—from months to years after the end of the current surge. If immunity is short-lived, as is the case for seasonal flu and colds caused by other coronaviruses, then there could be another wave of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the fall. The previous influenza pandemic—the swine flu H1N1 in 2009—had a second wave of infection after a winter-spring outbreak, Kissler points out. “There was still transmission over the summer, but it was lower. Then we saw a resurgence in the autumn,” he explains. Regarding SARS-CoV-2, he says, “We may have to do these social distancing measures again in the fall as the transmissibility rises again.”

If immunity lasts years, as was the case for the SARS-CoV-1 outbreak in 2003, or if there is some cross-immunity between this novel virus and other related coronaviruses already circulating within the general population, then it could be two or more years before a resurgence occurs. By then, there may be effective treatments or vaccines in place. In general, though, immunity tends to last longer when viruses incite a stronger immune response. Considering that people can have SARS-CoV-2 without symptoms, the extended-immunity scenario seems unlikely.

Kissler and his coauthors show that if immunity to SARS-CoV-2 is not permanent, it will probably enter into regular circulation among humans. That could mean people will need to deal with one or more resurgences over the next year, or that this disease could become another seasonal disease like the flu and various common colds.

Epidemiologists, including Kissler and his team, are actively studying the length of immunity to and the seasonality of SARS-CoV-2. The progression of COVID-19 infections over the summer will reveal the virus’s seasonality. Epidemiologists will need more time to determine how quickly immunity wanes. “We’re still months to even a year away from knowing for sure how the immunity is going to look,” Kissler says. In the meantime, epidemiologists will monitor viral outbreaks, to home in on remaining chains of transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Deciding where to implement testing for infection continues to be a pressing issue.

“These outbreaks can spread so explosively,” Kissler notes. That’s why social distancing has been important, and will continue to be so in any upcoming outbreaks. In the longer term, we will need to constantly adjust to new information and prepare to change our behavior permanently. “This virus may be with us for a very long time,” Kissler says, “and we need to think about what we can do to structure our own lives and even our society for the reality of this and of whatever other outbreaks come our way in the future.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.